Abstract

This paper analyzes the reasons behind the creation of the Drugs Diversion Pilot (DDP) program in West Berkshire, Thames Valley. The context of drug use and related deaths in the UK is provided, followed by a brief history of drug policy development in the UK, and the evolution of the ‘British system’ over time. The paper then highlights recent policy shifts towards drug possession at a local level, driven by police forces, rather than the central government. Three innovative schemes by different forces in England and Wales are examined to develop a rationale for the development of the Thames Valley Police (TVP) initiative. Additionally, the paper discusses the importance of a daily alcohol detox program to combat alcohol addiction.

The initial results of the TVP DDP show that although only one individual refused outright to attend a programme of treatment, 55% of those eligible did not enter into treatment (initially accepting an offer of treatment and then not engaging with the provider).

However, of those who did agree, all attended an initial assessment and, of those, only two individuals failed to complete the subsequent three treatment sessions.

By comparing the justice outcomes issued during the DDP to a similar time period in the same locality when the DPP was not available, 67% of those found in possession of drugs prior to the DPP starting would not have received a sanction affording them access to treatment. Those attending treatment report that it made them think differently about drug use and having improved perceptions of procedural justice, and officers administering the scheme found it easy and efficient to use.

Introduction

Drug policy in the United Kingdom has been based upon the twin pillars of law enforcement and the simultaneous provision of treatment for addiction. This approach has persisted since the late 19th Century. In the last 30 years however there has been an exponential rise in problematic drug use.

whilst enforcement continues to be central to policy, over the last decade there has been a shift towards the treatment of persons found in possession of drugs by the police rather than criminalisation through traditional criminal justice routes and available disposals.

Against this backdrop, whilst enforcement continues to be central to policy, over the last decade there has been a shift towards the treatment of persons found in possession of drugs by the police rather than criminalisation through traditional criminal justice routes and available disposals.

This policy change has been most recently led by four police forces (including the Thames Valley) in separate regions of England and Wales. The emphasis of these policies is on providing individuals with an opportunity to avoid the stigma of receiving a criminal record, whilst at the same time offering incentives to attend drug diversion programmes and treatment.

As the shift towards treatment over criminalization continues, more and more individuals are seeking out help for addiction. However, finding the right rehab center can be a daunting task. Fortunately, facilities like WhiteSands rehab centers offer a range of evidence-based treatment options tailored to the individual’s unique needs. With a focus on holistic healing and long-term recovery, rehab centers like WhiteSands can provide a safe and supportive environment for individuals struggling with addiction to begin their journey toward healing and wellness. By working together, law enforcement and treatment providers can help ensure that those struggling with addiction receive the help and support they need to overcome their challenges and lead healthy, fulfilling lives.

Three of these approaches constitute deferred prosecution schemes and have been put in place by Avon and Somerset, West Midlands and Durham Constabularies. The fourth scheme trailed by Thames Valley Police is novel in that it utilises current legal frameworks that are nationally endorsed, has lower administration costs than deferred prosecution schemes and current polices, constitutes a voluntary mechanism for attendance, and offers the potential for persons found in possession of drugs to be subject to multiple referrals.

Context

The United Kingdom has the third highest levels of drug related deaths per capita in Europe (EMCDDA, 2018) and has the highest drug dependency in the European Union (EMCDDA, 2018). The ‘British System’ (Pearson, 1991; Ashton & Witton, 2003; British Medical Association, 2013) aimed at tackling drug use has been characterised by a dual approach of medical intervention sitting within a criminal framework. The latter has been focused on prohibition. The aim of drugs prohibition is to prevent individuals from possessing and using drugs in order to protect their health, prevent harm to others and to prevent the spread of crime associated with drug use (Clutterbuck, 1995; Husak, 2003; Husak & De Marneffe, 2005; Sher, 2010).

Proponents of prohibition and punishment of possession of drugs argue that a more tolerant approach to drugs through legalisation would make it more socially acceptable to use them.

The use of drugs by individuals is linked to both mental and physical health issues (Stevens, 2007; Ruback & Clark, 2013), victimisation in crime (Stevens, 2007; French, 2015; Clausen, 2017) as well as a higher propensity to commit crime (Best, 2003; March, 2005; Oteo, 2015).

The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 follows this logic of protecting drug users by classifying drugs that cause greater harm to individuals in higher categories and imposing harsher sentencing for those ‘higher category’ drugs (The Police Foundation, 2000; Ward, 2013). It acts to serve as a deterrent to possession thereby minimising harm to individuals. The second strand of the ‘British system’ of providing treatment by medical practitioners, health care professionals and intervention programmes is aimed at firstly preventing individuals from becoming involved in illicit drugs and secondly reducing users’ dependency if they have an existing relationship with drugs (Pearson, 1991; Ashton & Witton, 2003; British Medical Association, 2013). Proponents of prohibition and punishment of possession of drugs argue that a more tolerant approach to drugs through legalisation would make it more socially acceptable to use them. This would be associated with a rise in usage and subsequently more damage to the individuals using the drugs and related damage to society (Van Dijk, 1998; Korf, 2002).

There are strong arguments to support the hypothesis that harsher penalties for possession do not reduce subsequent drug possession or deter use (Clutterbuck, 1995; UK Drug Policy Commission, 2008; Albrecht & Ludwig-Mayerhofer, 2011) and the evidence for this in the UK is supported by international studies.

Furthermore, it is argued that rather than deter those persons who are dealt with by the police through the application of the Misuse of Drugs Act (1971) or other legislation connected to prohibition of drug use, the stigmatisation of having a criminal record or sanction for possession of drugs marginalises them and prevents their reintegration into the social and economic community (Collinson, 1993; Buchanan & Young, 2009; Ward, 2013).

Alternative approaches to prohibition have been suggested, including decriminalisation, licensing or legalisation (Clutterbuck, 1995). Crucially if the raison d’etre behind the legislation is to protect individuals from harm but other strategies are more successful and cost efficient then these should be considered in lieu of enforcement of prohibition (Bueermann, 2012; Ward, 2013).

There is evidence to suggest that rehabilitation can influence re-offending and currently prevents an estimated 4.9 million crimes nationally every year

The government 2017 evaluation of the ‘Drug Strategy 2010’ surmised that: “there is, in general, a lack of robust evidence as to whether capture and punishment serves as a deterrent for drug use” (p.103, HM Government, 2017) Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that rehabilitation can influence re-offending and currently prevents an estimated 4.9 million crimes nationally every year (NHS, 2017). Public Health England evaluates that for each £1 spent on drug treatment, there is an estimated benefit of £2.50 to society. This is, however, not all crime related and is also linked to health and positive employment outcomes (Public Health England, 2017)).

In line with the above empirical research, there appears to be a growing social appetite for alternative approaches that may work better than enforcement and prohibition (Clutterbuck, 1995; Husak & De Marneffe, 2005; Albrecht & Ludwig-Mayerhofer, 2011). There are risks to taking such approaches.

Firstly, decriminalisation may increase the uptake in drug usage and as a consequence create more harm than continuing with enforcement of legislation (Husak & De Marneffe, 2005).

Secondly, if this does happen and a decision is made to re introduce legislation prohibiting drugs possession, it may be difficult and take more resources to ‘regain control’ (Clutterbuck, 1995). These arguments may have more pertinence to young persons or children who are viewed as not having full cognitive ability or appreciation of choices that they make.

New drivers in policy changes

The development of law enforcement policy in England and Wales is complex. Central government is able to drive policy through legislation, Home Office Circulars, Ministry of Justice directives and influence behaviour through key performance indicators and financial incentives.

In separation to this, policy makers and drivers exist at a national level who are independent of the government – historically, the National Police Improvement Agency and the Association of Chief Police Officers and currently the National Police Chief’s Council (NPCC) and the College of Policing (Neyroud, 2009; Heaton & Tong, 2016).

Middle level actors, comprised of individual police forces, chief constables and Police and Crime Commissioners are able to ascribe priorities to national policies, determine their uptake, but also drive their own strategic direction (Loader & Sparks, 2002; Heaton & Tong, 2016).

Finally at an individual level, officers have a great deal of discretion as to whether to enforce directives and legislation. The drive for policy change, however, has shifted over time to a greater emphasis on ‘evidence based policing’ and ‘what works’ (Raynor, 2002; Bullock & Tilley, 2009; Neyroud & Wiesburd, 2014; Heaton & Tong, 2016). This direction has not been solely taken by national actors but has also involved police forces themselves creating and employing their own policies on the basis of academic research and evidence from trials (Dawson & Williams, 2009; Sherman, 2012; Neyroud, Slothower, Sherman, Ariel, & Neyroud, 2017; Routledge & Weir, 2019).

If the person abides by the conditions that have been set by the police, then the prosecution in whatever form that may take is not enacted.

Four such notable schemes in relation to drugs have included: The ‘Drug Education Programme’ (DEP) instigated by Avon and Somerset Constabulary, The ‘Drug Diversion Pilot’, (DDP) run by Thames Valley Police (both of which have been aimed exclusively at individuals found in possession of drugs), ‘Turning Point’ implemented by West Midlands Constabulary and ‘Checkpoint’ run by Durham Constabulary.

The DEP, Checkpoint and Turning Point, are all similar in that they are ‘deferred prosecution’ schemes. The concept of a deferred prosecution scheme is for conditions to be set for an individual to abide by or complete. If the person abides by the conditions that have been set by the police, then the prosecution in whatever form that may take is not enacted. Furthermore, there is no record of the offence taking place recorded against the individual’s name if they comply. In this way the stigmatisation involved in a person obtaining a criminal record is avoided.

In the absence of fulfilling the conditions, however, the suspect is prosecuted. In the case of the DEP, Turning Point and Checkpoint, this involved the individual being charged or summonsed with an offence and being taken to court.

Outside of these three pilots, deferred prosecution currently functions in England and Wales under the legislative framework of ‘conditional cautions’. These were introduced in 2003 under the Criminal Justice Act, 2003. The ‘conditional caution’ allows officers to impose conditions on an offender which, if not fulfilled, result in the offender being prosecuted.

However, in contrast to the above three schemes, the conditional caution as with a ‘simple caution’ nevertheless remains and constitutes a criminal record, even if the conditions are fulfilled. It is argued that the stigmatisation of having a criminal record for drug use marginalises individuals and prevents their re-integration into the social and economic community (Collinson, 1993; Buchanan & Young, 2009; Ward, 2013). For this reason, the application of conditional cautions as a type of deferred prosecution has been seen to be unsatisfactory.

Thames Valley Police Drug Diversion Pilot (DDP)

The ‘DDP’ implemented by TVP differs from other approaches on the basis that it is a voluntary referral scheme that functions within the constraints of current nationally accepted legal frameworks.

Within the criminal justice system in England and Wales in addition to ‘cannabis warnings’ there are a number of ‘Out of Court Disposal’ (OOCD) options that can be employed by the police in lieu of charging people to appear at court. This includes ‘simple cautions’, ‘conditional cautions’, ‘fixed penalty notices’ (FPNs), ‘adult restorative disposals’, ‘youth restorative disposals’ and ‘youth cannabis warnings’. Nationally, approximately one third of all current recorded disposals are through these OOCDs (Sosa, 2012).

The ‘DDP’ implemented by TVP differs from other approaches on the basis that it is a voluntary referral scheme that functions within the constraints of current nationally accepted legal frameworks.

Following the introduction of conditional cautions in 2003, the second important institutional development in OOCDs was the introduction of a ‘community resolution’ by the Home Office (2013). This is a non statutory, OOCD option for officers to utilise nationally. It is the introduction of ‘community resolutions’ that has allowed for a new approach to be trialled in relation to drug possession offences by the police. Community resolutions do not lead to a criminal record. In this sense, in relation to drug offences, they are equivalent to a Cannabis Warning, a FPN and the deferred prosecution schemes described above.

The advantage of the ‘community resolution’ is threefold. The first is that any application of a ‘community resolution’ does not result in a criminal record and thus avoids the damaging stigmatisation of offenders referred to above (Collinson, 1993; Buchanan & Young, 2009; Ward, 2013).

The second is in relation to the savings that can be made in resources in using them in contrast to cautions, charges and deferred prosecution schemes. As no prosecution is threatened, there is no necessity to gather evidence of the offence for the purpose of presenting it in court. Moreover, ‘community resolutions’ are not limited in their application to cannabis and can theoretically be applied to any drug type.

Finally, ‘community resolutions’ in contrast to cannabis warnings can involve voluntary conditions set by the officer in the case. Conditions can be far reaching (NPCC, 2017) and can certainly include a requirement to attend a drug service provider to address drug dependency issues. However in contrast to the deferred prosecution schemes, the adherence to any conditions set by the officer by the suspect is voluntary. This avoids the coercive element that has been argued to be both unethical and ineffective in the treatment of drug addiction (Klag, O’Callaghan, & Creed, 2005; Braithwaite, 2011; Camerion, Wolfe, & Hyshka, 2012).

The obvious question can be posed, that if there is no consequence to not adhering to conditions, why would a suspect who has committed an offence observe them? It is useful at this juncture to compare the voluntary community resolution outcome with conditions to attend a drug diversion scheme to a cannabis warning. The practical application of a ‘cannabis warning’ is just that, a warning that the next time the individual caught is found in possession of cannabis they will receive a more punitive outcome, whether that be a fixed penalty notice or a caution.

The voluntary mechanism of attendance is given gentle impetus by offering an incentive to attend the drug service provider.

This is in practice delivered either verbally or in writing by the officer dealing with case. In this sense a move to a two tier OOCD outcome in relation to cannabis offers a greater disincentive to re-offend than a cannabis warning. In opposition to a cannabis warning where the next contact with the police would normally entail a fixed penalty notice, in a two tier system the next contact would entail a conditional caution presenting a further opportunity to engage an individual in a programme of treatment.

Adjustment of the community resolution mechanism

The voluntary mechanism of attendance is given gentle impetus by offering an incentive to attend the drug service provider. In contrast to the framework put forward by the NPCC (NPCC, 2017), as long as the conditions are adhered to, the individual found in possession of drugs is informed that they will be eligible for another referral. If they do not adhere to the conditions of attendance at a drug service provider they will not be. This is both a ‘carrot’ and a ‘stick’. A stick because the threat hangs over them that if found with drugs again they will be more severely dealt with if they don’t attend. A carrot because if they attend, they have the opportunity of the same resolution if caught another time.

Once this adjustment is applied, the community resolution becomes a tool that offers incentives for an individual found in possession of a drug for voluntary submission to a drug service provider, that are not present in a cannabis warning.

From a practical perspective this was seen as important for three reasons. The first, is that an individual may be referred and not have had the opportunity to attend their appointment before they are caught again. The second is that even if an individual has attended and is in treatment, treatment is not an instantaneous process. For example, the issuing of a pharmacological treatment for heroin from first contact with an individual can take up to 3 weeks.

If an individual is abiding by conditions, attending treatment, then there does not appear to be any benefit from issuing them with a criminal record.

A blood sample is needed, which then requires analysis at a lab, the results of which are subsequently sent to a G.P. to inform them of a suitable treatment and dosage of drugs. Whilst initial pharmacological treatment can be prescribed within three weeks, the tiering of the dosage to an appropriate level may take several more weeks. Third, the process of treatment of addiction is a process that may take a number of attempts prior to being successful and may also involve relapses (Barnes, 1988; Weddington, 1991; See, Fuchs, Ledford, & McLaughlin, 2003).

If an individual is abiding by conditions, attending treatment, then there does not appear to be any benefit from issuing them with a criminal record. As argued earlier, prohibition is a deterrent to possession. But if someone is already in possession of a drug then this deterrent has failed. If they are engaging in an activity to reduce their use of drugs, then the deterrent of criminalisation or further criminalisation can be used to better effect. In designing the scheme, a predicted rate of 40% attendance at the drug diversions scheme was anticipated. This was based on the attendance of youth to voluntary diversion schemes as a result of contact with the police and subsequently youth offending teams.

Eligibility for referral

The starting point for referral in the DDP was that all persons found in ‘possession of a controlled drug’ contrary to section 5 of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 would be eligible. As described above persons could be referred numerous times as long as they abided by the conditions of each referral. If, however, a person was referred and they did not attend the drug service provider and complete the required number of sessions, then they would not be eligible for further diversions. It should be noted that the coercive element present in this pilot is much lower than that seen in deferred prosecution schemes where the ‘sword of Damocles’ is seen to be at work (Neyroud & Slothower, 2015).

Whilst seemingly a simple process to follow, it was emphasised in the pilot that officer discretion within it was crucial for a number of reasons. First, officer discretion would be required for the initial decision as to whether a suspect is in possession of drugs for their own personal use or suspected of supply. It was considered whether nominal limits could be used such as are in place in Portugal where personal possession of drugs is deemed to be anything under 10 days use (Greenwald, 2009). However, it may be that a supplier of drugs is only carrying with them a small quantity of drugs that could be deemed to be for personal use, but through other evidence they are suspected by the officer dealing with them to be supplying (e.g. through the possession of scales, mobile phones, bags, etc.). Where supply of drugs was suspected, then the ethical reasons outlined above for the implementation of the pilot would not apply and thus diversion would not be appropriate.

Second, in whatever way an individual is to be dealt with, efforts to confirm their identity will need to be made. If a person is being considered for referral or summons to court, their identity will need to be ascertained in order to ensure that the correct suspect is recorded on police systems. If this were not completed and false details were provided by the offender, multiple issues will be caused for the administration of justice and for the functioning of the pilot study. Ascertaining the identity of a person outside of custody or a police station is done on a regular basis and officers are adept at the process. Situations where this is the case includes the issuing of fixed penalty notices for a number of different situations ranging from shoplifting, public disorder to driving related offences.

Third, it is necessary for officers to be able to exercise discretion if their professional knowledge directs them to suspect that an individual would be better safeguarded through arrest rather than diversion.

These three situations describe scenarios where the power of arrest can be exercised and where the ‘necessity criteria’ exist to do so under Code G of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984.

Fourth, in circumstances where a person was found in possession of drugs but was not living in the locality where the DDP was being implemented, diversion becomes problematic. The remit of the drug service provider is to serve the population of the local community and not those in other areas of the country. Travel for persons referred back to the locality where they were arrested also constituted a barrier to attendance. A lack of information sharing agreements and memorandums of understanding with drug service providers across the country meant that referral to their own areas was not possible.

Fifth, in a situation where a person presented a defence to possession of a drug, referral would not be appropriate. Under the Criminal Procedures Investigations Act 1996, police officers are bound to pursue reasonable lines of enquiry whether they point towards or away from a suspect. If a person raises a defence to an offence, then the police are duty bound to investigate this. Any investigation of this kind would remove the opportunity for a referral.

Finally, creating a process where officers were unable to exercise discretion within the constraints of the law, may have meant that the process set for them would be disregarded and discretion exercised in any case. This may have happened without the evaluators of the pilot being aware of it, which would in turn skew any subsequent analysis.

Preliminary results

The Drug Diversion Pilot has been running in the West Berkshire Local Policing Area since the 10th December 2018, with funding secured for it until September 2019. The cohort of persons referred for diversion up until the 10th March 2019 was and will be subject to continued evaluation. The initial results provide figures in respect of the number of referrals made, sources of referrals and overall attendance figures. A comparison is also made with data from the same period in the year before the pilot began (10th December 2017 and 10th March 2018) from the same geographical area as a control group.

Comparisons are made between the two groups in terms of the number of recorded offences and criminal justice outcomes. Re-offending rates from those in the control group are also analysed. The results highlight the lack of opportunity for drug users who come into contact with the police to engage in treatment resulting from criminal justice disposal options. 49 Comparison of offending rates in West Berkshire

Offences

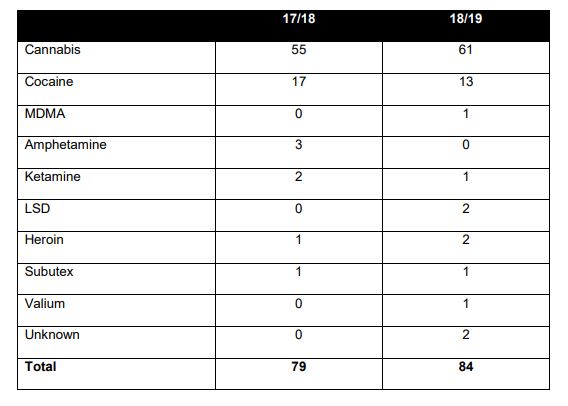

The table below shows the distribution of drug possession offences comparing the period 10/12/17 – 10/03/18 (acting as a comparison cohort) with the period of the pilot between 10/12/18 – 10/03/19 (pilot cohort).

Table 1: Possession of drugs offences in West Berkshire comparison between 10/12/17 – 10/03/18 and the period of the diversion pilot 10/12/18 – 10/03/19 17/18 18/19

There was some concern that the introduction of the diversion scheme might lead to an increase in drug use in the West Berkshire area. An assessment of whether there has been a rise in drug use in West Berkshire cannot be made by reference to police data alone because the majority of drug offences are identified through police activity.

Nevertheless the results do indicate the policing of drugs in West Berkshire was consistent during the pilot period compared with the same time period in the previous year (79 offences between 10 December 2017 and 10 March 2018 and 84 offences between 10 December 2018 and 10 March 2019). There is also similarity between the types of drugs found over the two periods examined. Figures from previous years were used to project the number of referrals to the drug service provider. The accuracy of these figures meant there were no issues with the drug service provider managing the demand from police referrals.

Referrals and attendance rates

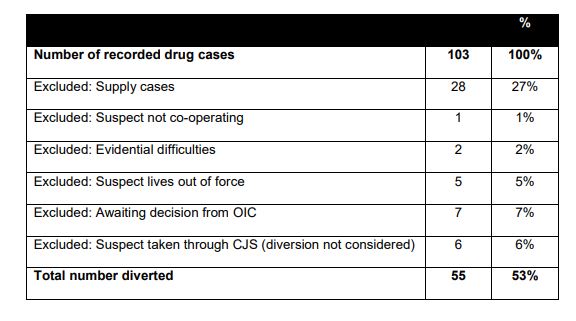

Table 2 shows the total number of drug cases recorded in West Berkshire LPA during the pilot detailing the reasons why some were not sent for diversion.

Table 2: Number of drug cases during the period of the pilot

Table 2 indicates that in most cases eligibility for the scheme was well understood by officers. 55 suspects (53%) dealt with for drug related offences were referred into a programme of treatment to address their use of controlled substances. Most of those who were not referred (27%) were suspected of being concerned in the supply of controlled substances. There was only one case where the individual refused to engage with the scheme at the outset. There are opportunities to increase the numbers eligible for diversion.

There are still seven cases (7%) awaiting a final disposal which could increase the final number of people sent for diversion. It is also of note that five individuals (5%) did not have the option for diversion because they did not live locally indicating that wider availability of diversion schemes could increase the number of people treated for their drug use.

There were six cases (6%) where diversion was not considered. These are cases dealt with by specialist units or officers covering from other police areas who were not aware of the existence of the diversion scheme.

Engagement with the service provider

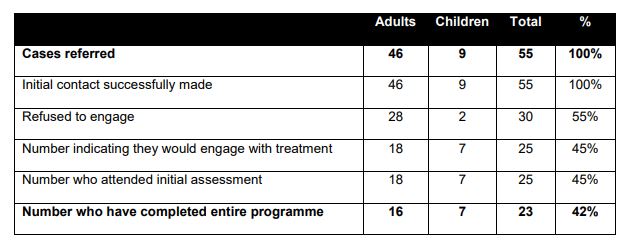

Table 3 shows the take up of the diversion scheme following an encounter with the police.

Table 3: Engagement with the drug service following referral by the police

Table 3 indicates the greatest attrition from the diversion scheme occurs between referral by the police and initial contact with the drug service provider. 30 (55%) people declined to engage when contacted. It is encouraging that all of those who indicated they would engage with the treatment attended an initial assessment. Only two of those subsequently failed to go on to complete the treatment programme. Overall, 23 out of 55 adult individuals (42%) completed the initial assessment followed by three additional treatment sessions. Seven out of nine children and young people (78%) (under the age of 18) completed the full programme of treatment.

The attendance rate of children and young people is particularly positive. The local Youth Offending Service are keen for this approach to continue into the future as a result of the success. Although there is no direct evidence that any of the children and young people referred through this scheme were either vulnerable to or being exploited, it is clear the diversion scheme allows for an intervention opportunity for children with these issues by offering specialist youth support. The approach also fits with the Government’s Serious Violence Strategy (April 2018) in which police were encouraged to review their approach to prosecution and diversion in relation to tackling drug exploitation and misuse of drugs.

Number of referrals by drug type

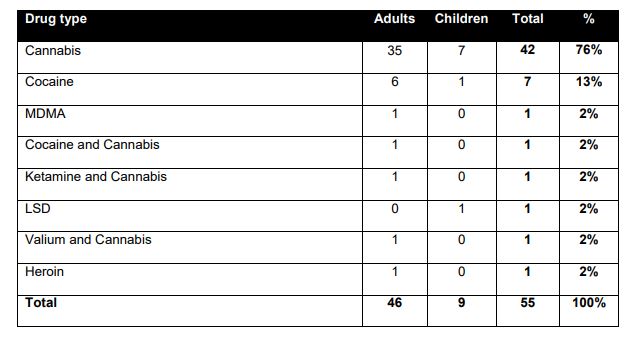

Table 4 shows the referrals by drugs type.

Table 4: Referrals to the drug service by drug type

Although the vast majority of referrals were for possession of Cannabis (61 representing 79% of the total), it can be seen that suspects were referred for a range of other drug types and some had more than one type of controlled substance. Interestingly, the drug service provider found that the referrals have led them to identify a number of underlying reasons for drug use which they have been able to address. If the diversion scheme identifies those who have not developed problematic drug use it seems likely that the treatment could represent early intervention and prevention of more harmful drug use which might occur in the future. 2 Some were suspected of possession of more than one type of drug.

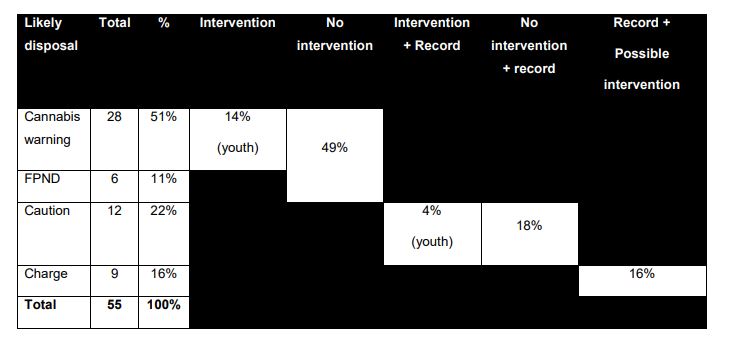

Outcomes without a drug diversion scheme

In the absence of a drug referral scheme each case was examined to identify what the likely outcome would have been for that particular individual.

Table 5: Likely disposal for 55 eligible cases without a diversion scheme

Table 5 shows that 37 people (67%) would have been given a sanction that with certainty did not afford an opportunity for them to address their drug use if the diversion scheme was not available. This relates to FPNs, cautions and cannabis warnings. This figure rises to 46 (84%) if as is likely no intervention were to be offered as part of sentencing conditions fixed by a court. In addition the ten (18%) who would have been likely to receive an adult caution would also end up with a criminal record. Only nine (16%) of those eligible under the piloted diversion scheme would have been given the definite opportunity through the Youth Offending Team to access any treatment for their drug use. The stigma associated with having a criminal record has been identified as a factor that marginalises users, preventing their reintegration into the social and economic community.

Feedback from those undertaking treatment

Those who attended treatment were asked by the drug service provider to complete a survey at the end of the treatment about their experience (in the knowledge this would be shared with the police). Comments provided by those undertaking the scheme allude to personal benefits and appear to increase perceptions of procedural justice, taken to be how an individual perceives a person in authority to apply processes in relation to them in a fair and just way (Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service, 2019):

“Overall I have benefited a lot from the scheme and am more aware of the hard work put in by the police now and am grateful for it.” (Individual 1)

“Being with others in the same position was good to communicate with and helped to realise stuff about myself.” (Individual 2)

“Completely changed my drug habits because of effects on family and my possible future. Was an eye opener.” (Individual 2)

“Learnt other side effects. Learning about other drugs I don’t intend on doing.” (Individual 3) “Dealt with very professionally.” (Individual 1)

“Wasn’t treated like a criminal, just told not to do it again.” (Individual 3)

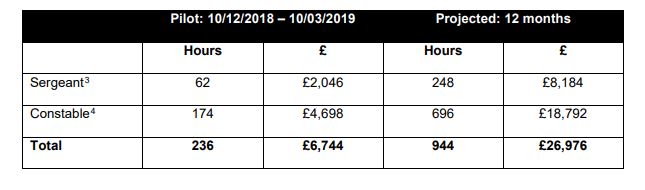

The drug service provider has related that three months following completion of the treatment programme, two of those that attended have self-reported that they are drug free. Savings Whilst savings are not the key driver of this initiative (the ultimate aim is to reduce the harm caused by substance misuse) there has been a reduction in costs, particularly in terms of officer time. Each case was reviewed to determine what would have happened to the suspect had the diversion scheme not been available in order to accurately estimate the savings shown in the table below.

Table 6: Estimated savings (non-cash) as a result of introduction of a diversion scheme versus CJS options

Table 6: Estimated savings (non-cash) as a result of introduction of a diversion scheme versus CJS options

Over the period of the pilot, non-cash savings totalled an estimated £6,744. If the results of the scheme are replicated over an entire year it is estimated the non-cash savings will amount to £26,976. Given this pilot took place in one of the smaller LPA’s it is likely that the non-cash savings would be considerable if implemented across the force. One of the aims of the diversion scheme was to enable officers to deal with cases of possession more quickly allowing them time to target those supplying drugs in our communities. There was direct evidence of this working in practice during the pilot study. During a dedicated operation, diverting one individual allowed officers to resume patrol quickly. This lead to the arrest of another individual suspected to be involved in the supply of drugs. The senior officer reported:

“The unit stopped some vehicles, two of which were carrying possession levels of drugs, one class B and one class A. The one carrying Class B was eligible for diversion, so was dealt with by the units at the roadside…. This took about ten minutes, with no long trip to custody. It meant they were then ready to deploy straight away. The other male [stopped after officers resumed], was arrested concerned in supply.”

Feedback from West Berkshire LPA staff

Feedback from staff delivering the pilot has been overwhelmingly positive. Using a section at the end of the online referral inviting feedback officers report that the scheme is simple and quick to administer. The following feedback has been provided by officers making use of the diversion scheme:

“I thought it was a good scheme when the training was delivered (& I can be cynical enough about a couple of things we’ve had over the years!)…. I thought it was pretty straight forward and I would definitely use it again.” (Case 20)

“It’s really easy and simple to use. So much quicker than what I would have had to do otherwise…. I would have had to send the drugs off for testing, RUI’d him, it would have been on my screen for 8 weeks. This was really easy. I like it.” (Case 2)

“I have used this a couple of times now…. I have found it really easy and quick. I have also had a thank you from a detainee that I dealt with to say he was sorry for his arrest and feels he was treated fairly.” (Case 24)

“Found it really simple, it’s nice something being implemented where it’s really easy and quick to do.” (Case 25)

“I found the scheme really good. I thought it was a great tool to have access to during my dealings with the male that had been detained. I will look forward to using this again especially as it was easy and straight forward as well.” (Case 40)

“The process itself is really straight forward. I was a little bit sceptical with the introduction of the diversion but I have been able to see the benefits over the last week.” (Case 56)

Conclusion

The last decade has seen policy in relation to those found in possession of drugs by the police shift, whilst remaining within the twin pillars of ‘enforcement’ and ‘treatment’ that has characterised the ‘British system’. This has seen a greater emphasis being placed on the treatment of addiction.

The most recent policy changes have seen the police themselves take a lead and four separate trials have taken place in different regions of England and Wales. Three of these pilots fall under the banner of ‘deferred prosecution’ schemes trialled by Avon and Somerset, Durham and West Midlands Constabularies.

The fourth and most recent is the DDP implemented by Thames Valley Police. This scheme in difference to the other three utilises a nationally accepted criminal justice disposal, that of the ‘community resolution’. In so doing it makes the process of referral voluntary with a view to increasing the efficacy of the intervention.

Under the DDP, being found in possession of drugs for personal consumption and being subject to a referral does not constitute a criminal record, avoiding the damage of the stigmatisation associated with having a criminal record. The model allows for officer discretion to be maintained, ensuring the ability to safeguard and to prosecute more serious offences. It also offers the potential of some non-cash savings in terms of officer time. Significantly, an admission to possession is not required by the suspect, potentially allowing increased participation by some ethnic minorities when compared to deferred prosecution models. Finally, in line with evidence around cycles of addiction, multiple referrals can take place.

The results show an overall attendance rate of 44% for those eligible and initially indicating a willingness to engage with the drug service provider. The attendance rate for children and young people was particularly notable at 78%.

Steps need to be taken to address the attrition between agreement to co-operate during the initial encounter with the police and engagement with the drug service provider. However, it is encouraging that of those who did engage with the drug service provider all underwent an initial assessment and a further 92% undertook the three treatment sessions.

The results show the majority of people dealt with for drug possession without the scheme in place receive an immediate disposal with no opportunity to address their underlying drug use. Only the small number referred to the Youth Offending Teams or those charged with an offence may receive some form of treatment but at the same time those charged or issued with a caution also receive a criminal record which has been shown to have negative consequences when it comes to economic and social reintegration.

The results from the control sample show that more than 1 in 3 (39%) found in possession of drugs go on to reoffend. Although it is too early to determine whether the diversion scheme has an impact on rates of re-offending, the scheme offers a valuable alternative to an immediate disposal with no follow up and the stigmatisation of a formal criminal record. Moreover, the administration of the scheme has received positive feedback from officers and users with some indication it improves perceptions of procedural justice.

About the Thames Valley Police Journal

This article appears in Volume 04, November 2019 of the Thames Valley Police Journal which showcases the academic research undertaken by officers and staff in Thames Valley Police. To access this and other volumes of the Journal, please click on the images below.

References for this article

Avon and Somerset Constabulary. (2017, July 28th). Bristol Drugs Education Programme. Retrieved from Avon and Somerset Police: https://www.avonandsomerset.police.uk/149787-bristol-drugseducation-programme

Barnes, D. (1988). Breaking the cycle of addiction. Science, Vol.241(4869), p.1029-1031.

Barton, A. (2003). Illicit Drugs. Abingdon: Routledge.

Bennett, T., & Holloway, K. (2005). Understanding Drugs, Alcohol and Crime. Maidenhead: Open University Press. Best, D. (2004). Delivering better treatment: What works and Why? London: NTA National Conference.

Braithwaite, J. (2011). The essence of responsive regulation. UBCL Rev., Vol.44, p.475.

British Medical Association. (2013). Chapter 5 – Drug policy in the UK: from the 19th Century to the present day. In BMA, Drugs of dependence: the role of medical professionals (pp. 87-95). London: BMA Board of Science.

British Medical Journal. (1909). Poisons and Pharmacy Act 1908. The British Medical Journal, 1(2506): 15-16.

Buchanan, J. (2006, Jan 1). Understanding Problematic Drug Use: A Medical Matter or a Social Issue. Retrieved from Glyndwr University Research Online: https://glyndwr.collections.crest.ac.uk/94/1/fulltext.pdf

Buchanan, J., & Young, L. (2000). The War on Drugs – A War on Drug Users. Drugs: Education, Prevention, Policy, 7(4): 409-422.

Bullock, K., & Tilley, N. (2009). Evidence-Based Policing and Crime Reduction. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, Vol.3(4), p.381-387.

Camerion, T., Wolfe, J., & Hyshka, E. (2012). Consent and Coercion in Addiction Treatment. In A. Carter, H. Wayne, & J. Illes, Addiction Neuroethics: the ethics of addiction Neuroscien Research and Treatment (pp. 153-174). London: Academic Press.

Dawson, P., & Williams, E. (2009). Reflections from a Police Research Unit – An Inside Job. Policing: A journal of Policy and Practice, Vol.3(4), p.373-380.

Derks, H. (2012). The invention of an English Opium Problem. In H. Derks, History of the Opium Problem: The Assault on the East (pp. 105-120). Leiden: Boston: Brill.

DIP Strategic Communications Team. (2008, February). national archives. Retrieved from webarchive.nationalarchives.gov: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100408140955/http://drugs.homeoffice.gov.uk/publication -search/dip/DIP-impact-evidence-round-up-v22835.pdf?view=Binary

EMCDDA. (2018). Overdose Deaths. Retrieved from European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/data/stats2018/drd_en

EMCDDA. (2018). Statistical Bulletin 2018, Opiods. Retrieved from Eurpoean Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/data/stats2018/pdu_en

Hancock, J., Fearon, C., McLaughlin, H., & Fielden, B. (2012). Policing the ‘Drugs Intervention Programme’ (DIP): An exploratory study of the Southern UK policing region. Policing, 431-442.

Heaton, R., & Tong, S. (2016). Evidence-Based Policing: From Effectiveness to Cost-Effectiveness. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, Vol.10(1), p.60-70.

UK Treasury. (2015). Treasury Cannabis Regulation. Retrieved from Treasury: www.tdpf.org.uk/sites/default/files/Treasury-cannabis-regulation-CBA.pdf

Home Office. (2010, March ). Operational Porcess Guidance for implementation of Testing on Arrest, Required Assessment and Restriction on Bail. Retrieved from assets.publishing.service.gov.uk: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/977 92/DTOA-Guidance.pdf

Home Office. (2014, July). The heroin epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s and its effect on crime trends – then and now. Retrieved from Home Office: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/332 952/horr79.pdf

Home Office. (2018, April 9). Government Publications. Retrieved from Policy Paper: Serious Violence Strategy: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/serious-violence-strategy

Independent Drug Monitoring Unit. (2001, October 23). Home Office Press Release 255/2001, 23 October 2001. Retrieved from idmu.com: http://www.idmu.co.uk/oldsite/homeoffpr.htm

Independent Inquiry into the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. (2000). Drugs and the Law: Report of the Independent Inquiry into the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. London: The Police Foundation.

Klag, S., O’Callaghan, & Creed, P. (2005). The use of legal coercion in the treatment of substance abusers: An overview and critical analysis of thirty years of research. Substance Use and Misuse, Vol.40(12), p.1777-95.

Lammy, D. (2017). The Lammy Review: An independent review into the treatment of, and outcomes for, Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic Individuals in the Criminal Justice System. London: HM Government.

Lloyd, C. (2008). The Cannabis Classification Debate in the UK: Full of Sound and Fury, Signifying nothing. Second Annual Conference of the International Society for the Study of Drug Policy. Internation.

Loader, I., & Sparks, R. (2002). Contemporary Landscapes of Crime, Order, and Control: Governance Risk and Globalization. In M. Maguire, R. Morgan, & R. Reiner, The Oxford Handbook of Criminology (pp. 83-111). Oxford : Oxford University Press.

May, T., Duffy, M., & Hough, M. (2006). Policing cannabis as a class C drug: An arresting change? . Drugs and Alcohol Today, 6(4), 30-36.

May, T., Duffy, M., Turnbull, P., & Hough, M. (2002). The policing of Cannabis as a Class B Drgu. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

May, T., Duffy, M., Warburton, H., & Hough, M. (2007). Policing Cannabis as a Class C Drug: An Arresting Change. UK: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

McSweeney, T., Stevens, A., Hunt, N., & Turnball, P. (2007). Twisting Arms or a Helping Hand? Assessing the Impact of “Coerced” and Comparable “Voluntary” Drug Treatment Options. British Journal of Criminology, 47(3): 470-490.

Mills, J. (2008). Cannabis Nation: Control and Consumption in Britain, 1928-2008. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Neyroud, P. (2009). Squaring the circles: research, evidence, policy-making, and police improvement in England and Wales. Police Practice and Research, 437-449.

Neyroud, P., & Slothower, M. (2013). Operation Turning Point: Interim Report on a Randomised Trial in Birmingham. Cambridge: Cambridge: Institute of Criminology.

Neyroud, P., & Wiesburd, D. (2014). Transforming the Police through Science: Some New Thoughts on the Controversy and Challenge of Translation. Washington DC: George Mason University.

Neyroud, P.W. and Slothower, M.P. (2015), ‘Wielding the Sword of Damocles: The Challenges and Opportunities in Reforming Police Out-of-Court Disposals in England and Wales’, In Wasik, M. and Santatzoglou, S. (Eds.) The Management of Change of Criminal Justice: Who knows best? Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 275-293.

Neyroud, P., Slothower, M., Sherman, L., Ariel, B., & Neyroud, E. (2017, December 19). Operation Turning Point. Retrieved from College of Policing: http://whatworks.college.police.uk/Research/Research-Map/Documents/TP_Storyboard.pdf

NHS. (2017, Febuary 28). Statistics on Drug Misuse: England, 2017. Retrieved from National Archives: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20180328135520/http://digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB23442

Office for National Statistics. (2018, August 6). Deaths related to drug poisoning in England and Wales: 2017 registrations. Retrieved from Office for National Statistics:

https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/de athsrelatedtodrugpoisoninginenglandandwales/2017registrations

Pearson, G. (1991). Drug-Control Polices in Britain. Crime and Justice, 14:167-227.

Police National Legal Database. (2018, March 23). Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 – restriction of possession of controlled drugs. Retrieved from Police National Legal Database: https://docmanager.pnld.co.uk/content/D2104.htm

Prendergast, M., Podus, E., Chang, E., & Urada, D. (2002). The effectiveness of Drug Abuse Treatment: A Meta-analysis of Comparison Group Studies. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 67(1): 53-72.

Raynor, P. (2002). Community Penalties: Probation, punishments and ‘what works’. In M. Maguire, R. Morgan, & R. Reiner, The Oxford Handbook of Criminology (pp. 1168-1206). Oxford : Oxford University Press.

Reuter, P., & Stevens, A. (2008). Assessing UK drug policy from a crim control perspective. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 8(4):461-482.

Reuter, P., & Stevens, P. (2008). Assessing UK drug police from a crime control perspective. Criminology and Criminal Justice, 8(4): 461-482.

Robertson, R. (1987). Heroin, Aids and Society. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Routledge, G., & Weir, K. (2019). Checkpoint: An innovative Programme to Navigate People Away from the Cycle of Reoffending: Implementation Phase Evaluation. Policing: A journal of Policy and Practice, 1- 20.

Savage, S. (2003). Tackling Tradition: Reform and Modernisation of the British Police. Contemporary Politics, 9(2): 171-184.

See, R., Fuchs, R., Ledford, C., & McLaughlin, J. (2003). Drug addiction, relapse, and the amyglada. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Vol.985(1), p.294-307.

Sherman, A. (2012). Operation “BECK” Results from the First Randomised Controlled Trial on Hotspot Policing in England and Wales. 5th International Evidence Based Policing Conference 9 – 11 July 2012. http://www.crim.cam.ac.uk/events/conferences/ebp/2012/beckrctresults.pdf

Shiner, M. (2010). Post-Lawrence Policing in England and Wales: Guilt, Innocence . British Journal of Criminology, 50(5): 935-953.

Shiner, M. (2015). Drug policy reform and the reclassification of cannabis in England and Wales: a cautionary tale. International Journal of Drug Policy, 26(7). pp.696-704.

South, N. (2007). Drugs, Alcohol and Crime. In M. Maguire, R. Morgan, & R. Reiner, The Oxford Handbook of Criminology (pp. 810-838). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

The Police Foundation. (2000). Drugs and the Law: Report of the Independent Inquiry into the Misues of Drugs Act 1971. London: The Police Foundation.

UK Treasury. (2015). Treasury Cannabis Regulation. Retrieved from Treasury: www.tdpf.org.uk/sites/default/files/Treasury-cannabis-regulation-CBA.pdf

Ward, J. (2013). Punishing Drug Possession in the Magistrates’ Courts: Time for a Rethink. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 19(4): 289-307.

Weddington, W. (1991). Towards a rehabilitation of methadone maintenance: Integration of relapse prevention and aftercare. International journal of the addictions, Vol.25(9), p.1201-1224.