Amid the horror of these events and the following media debates, it is important not to lose sight of Australia’s many successes in tackling knife crime.

Across five days in April 2024, seven people were killed in five separate knife-related attacks in Sydney.

Two in particular caught huge media attention: the deadly Westfield Bondi attacks and the Wakeley church attack on Bishop Mari Emmanuel.

Three further attacks, including a stabbing that left one teenager dead, deepened the suspicion of worsening knife crime.

But amid the horror of these events and the following media debates, it is important not to lose sight of Australia’s many successes in tackling knife crime, let alone the far more lethal question of gun crime.

Fears of a worsening situation

In the months that followed, the media reported a wave of knife-related crimes. This included:

- a heightened focus on machetes following a gang fight in a central Melbourne shopping centre in May

- in Sydney, the stabbing of a 21-year-old man

- in Brisbane, a man was stabbed and murdered at a house party.

In each incident, the suspects arrested were teenagers.

These events have put the spotlight on knife crime and has already led to the fast-tracking of a ban on machetes in Victoria, and tightening legislation in New South Wales on knife possession and powers to search would-be suspects.

The rapid succession of these events led to New South Wales Police Commissioner Karen Webb stating in the aftermath of the Wakeley church attack: “Knife crime is an issue that has been on the agenda across Australia and New Zealand for many months and years now. It’s not new.” So, what does the data say about the broader trends?

What are the trends in Australia?

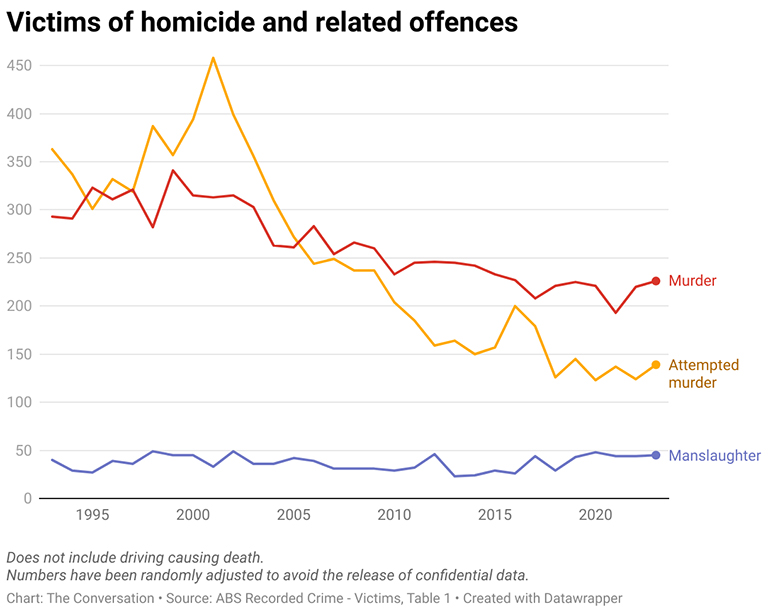

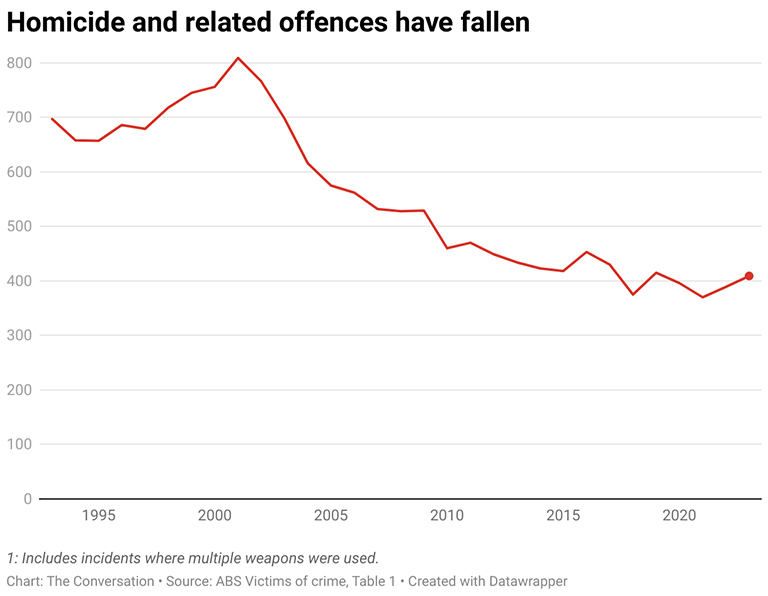

Crime trends, particularly the most violent crime, have largely fallen over the past two decades. The exception to this trend is family, domestic and sexual violence, which remains an urgent concern and, given its complexity, deserves separate attention.

Despite this, overall trends in crime, including the most violent, have fallen dramatically since the 1990s. This is part of a global pattern that criminologists call “the great crime drop”.

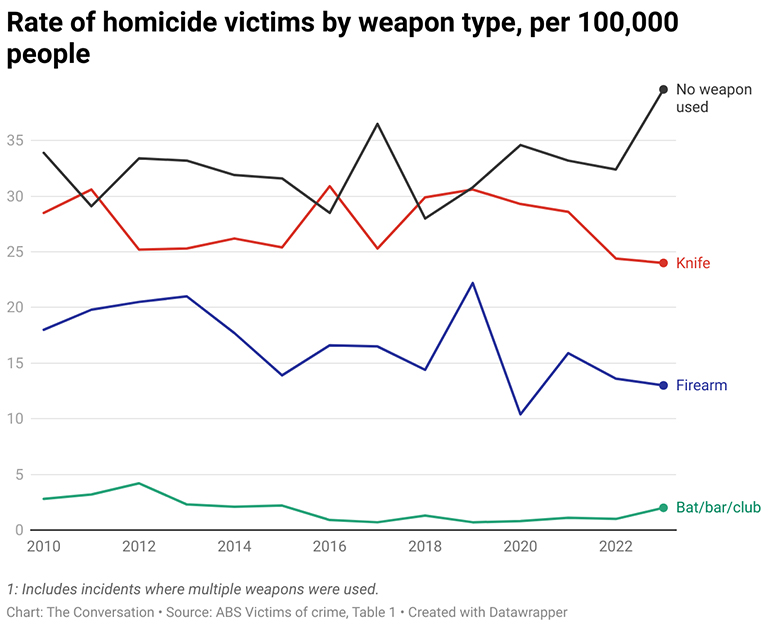

With less violent crime, there is going to be a corresponding drop in use of weapons. Even so, Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data shows a proportional decrease in the use of both firearms and knives in violent offences.

With less violent crime, there is going to be a corresponding drop in use of weapons. Even so, Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data shows a proportional decrease in the use of both firearms and knives in violent offences.

In 2023, just 13% of these incidents involved a firearm (down from a high of 22% in 2019), while 24% involved a knife (down from a high of 34% in 2018). In 34% of cases, no weapon was used.

The data underlines a general decline of knife and firearm use.

The data underlines a general decline of knife and firearm use.

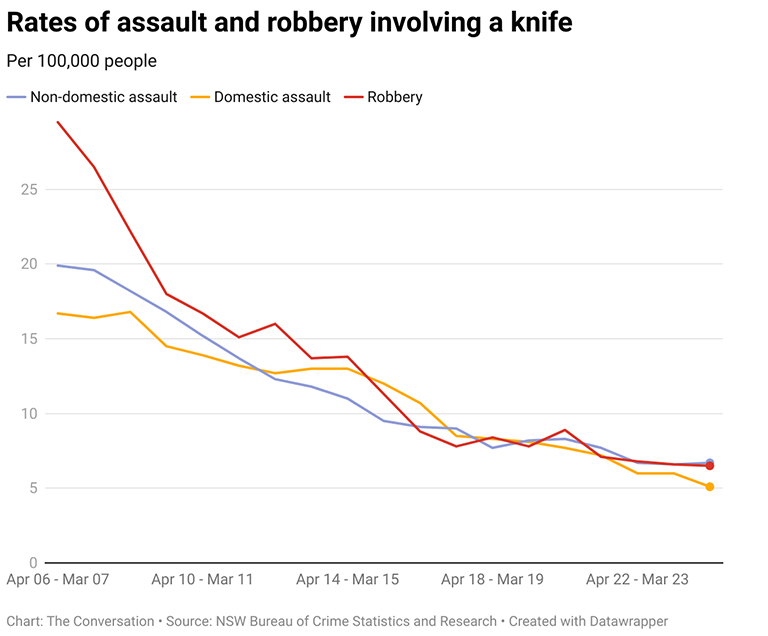

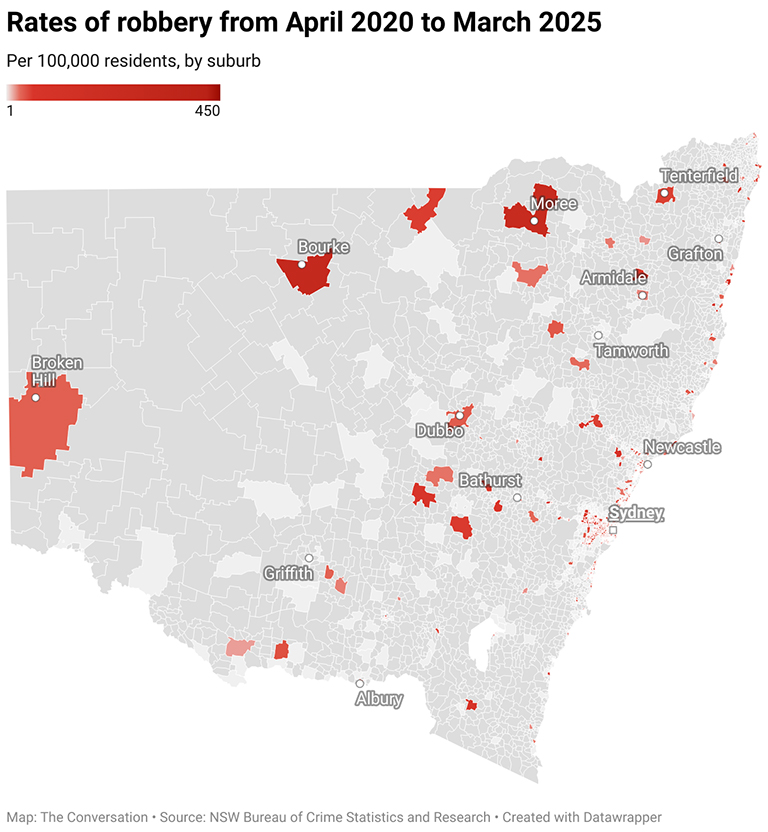

In NSW, data from the Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) paints a very similar picture of stable or declining weapon use across a range of violent offences. Yet it also reveals the geographical inequality of where such weapons are used, particularly for robbery.

In NSW, data from the Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) paints a very similar picture of stable or declining weapon use across a range of violent offences. Yet it also reveals the geographical inequality of where such weapons are used, particularly for robbery.

The mapping of these incidents tells a story of localised, rather than general, risk: robbery is fairly evenly clustered around population dense areas of central Sydney, Liverpool, Parramatta and the corridor to Penrith.

Robbery with a firearm is, of course, much rarer but it is heavily concentrated in just one suburb, Claymore, which sits north of Campbelltown to Sydney’s south.

Robbery with a firearm is, of course, much rarer but it is heavily concentrated in just one suburb, Claymore, which sits north of Campbelltown to Sydney’s south.

Between April 2024 to March 2025, data shows Claymore had 79 robberies involving a firearm per 100,000 residents. The next highest suburb, Kingswood, had only 26 incidents per 100,000.

The mapping of robberies with a weapon not a firearm – most typically a knife – again reveals further localised patterns. This points to a need for more targeted, community focused initiatives, rather than blanket restrictions and search powers.

What about similar countries?

Although firearm and knife restrictions are state and territory based, Australia still has some of the toughest in the world.

By global comparisons, gun ownership in Australia is relatively low. Data from the Centre for Armed Violence Reduction estimates Australia ranks below France and above Denmark, but still has almost three times the number of licit and illicit firearms than the UK.

Firearm restrictions and licensing was largely a reaction to the 1996 Port Arthur massacre, when 35 were killed by a lone gunman.

However, data from the Australia Institute estimates more firearms are owned by civilians today than before the Port Arthur massacre. Of course, Australia’s population has grown from around 18 million in 1996 to 28 million today.

Despite this, by global comparisons, gun ownership in Australia is relatively low. Data from the Centre for Armed Violence Reduction, for example, estimates Australia ranks below France and above Denmark, but still has almost three times the number of licit and illicit firearms than the UK.

The US remains the global outlier on gun ownership in the developed world, with a staggering estimated 121 firearms per 100.

Comparing deaths from stabbing globally is much more difficult. However, available estimates generally highlight, once again, the relative safety of Australia.

What more can be done?

It is important not to minimise the tragedies and harms still routinely caused by knife and firearm violence across Australia. However, the data shows how Australia’s efforts to restrict weapon use has been largely successful.

But more can be done. More rigid enforcement of existing laws is not enough; it must also include significant investment in preventative measures.

Providing young people with positive alternatives to crime, such as education, employment opportunities, and mental health support, is crucial to breaking the cycle of violence that is all too often localised.

This is about seeking out and implementing solutions that address the symptoms of this violence as well as the root causes that drive it.

The authors would like to thank the Centre for Armed Violence Reduction for sharing their data and contributing to this article.

Weapons and violence are rarely out of the media cycle in Australia, leading many to fear this country is becoming less safe for everyday people. Is that really the case, though? This is the second story in a four-part series from The Conversation (republished under a Creative Commons Licence).

Weapons and violence are rarely out of the media cycle in Australia, leading many to fear this country is becoming less safe for everyday people. Is that really the case, though? This is the second story in a four-part series from The Conversation (republished under a Creative Commons Licence).

About the Authors

Dr Alex Simpson is Associate Professor in Criminology at Macquarie University; his work focuses on the criminology of harm, cultural marginalisation and the sociology of political economy. Alex undertook his PhD at the University of York; this ethnographic study examines the culture of finance and the neutralisation of deviance within the City of London. He was also part of a British Academy funded, ethnographic study of class-based experiences of dirt and dirty work. Out of this critical engagement, Alex has a keen interest in qualitative research methods, including ethnography, photographic representation and elicitation, critical discourse analysis and in depth interview techniques.

Dr Alex Simpson is Associate Professor in Criminology at Macquarie University; his work focuses on the criminology of harm, cultural marginalisation and the sociology of political economy. Alex undertook his PhD at the University of York; this ethnographic study examines the culture of finance and the neutralisation of deviance within the City of London. He was also part of a British Academy funded, ethnographic study of class-based experiences of dirt and dirty work. Out of this critical engagement, Alex has a keen interest in qualitative research methods, including ethnography, photographic representation and elicitation, critical discourse analysis and in depth interview techniques.

Dr Vincent Hurley is a Lecturer in Criminology, Police and Policing at Macquarie University, whose lecturing and research area of expertise is the role of the police and policing within the dynamics of a nation states political environment. Vince commenced life as an academic after 29 years as a NSW Police Officer; he worked in street policing and as a Detective, and in an organised crime unit. He was also a Police Hostage Negotiator for eight years, the Director of Detective Training for the NSW Police Force, and developed state-wide policing strategies to reduce crime in NSW.

Dr Vincent Hurley is a Lecturer in Criminology, Police and Policing at Macquarie University, whose lecturing and research area of expertise is the role of the police and policing within the dynamics of a nation states political environment. Vince commenced life as an academic after 29 years as a NSW Police Officer; he worked in street policing and as a Detective, and in an organised crime unit. He was also a Police Hostage Negotiator for eight years, the Director of Detective Training for the NSW Police Force, and developed state-wide policing strategies to reduce crime in NSW.

Picture © ChameleonsEye / Shutterstock