Research released by the Australian Institute of Criminology provides stark evidence for why we must not let combating sexual violence fall off the national agenda.

Violence against women has been declared a national crisis in Australia. National Cabinet convened its first ever meeting focused solely on the issue in May.

Framed by its commitment to delivering the National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children, state and federal governments have committed to an array of different policies.

Sexual violence has, however, received less attention from the media and in political commentary of late. Research released by the Australian Institute of Criminology recently provides stark evidence for why we must not let combating sexual violence fall off the national agenda.

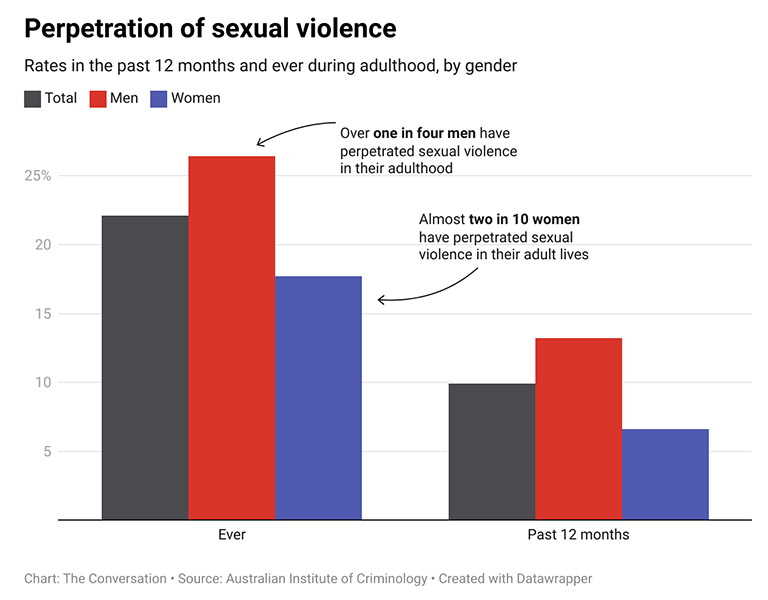

Shockingly, the study found one in five (22.1%) participants had perpetrated one or more forms of sexual violence against another person since the age of 18. One in 10 (9.9%) had done so in the past 12 months.

The prevalence of sexual violence

The study by the Australian Institute of Criminology is one of the largest community surveys conducted in Australia to focus on sexual violence perpetration. It surveyed 5,076 Australian residents aged 18-45 years about their use of various forms of sexual violence.

The survey defined sexual violence broadly to include sexual harassment and coercion, sexual assault and image-based sexual abuse.

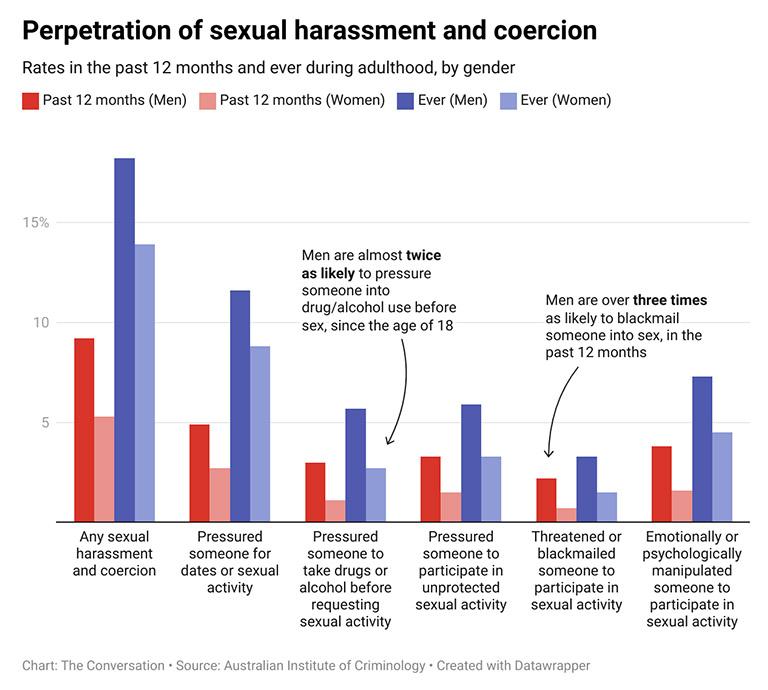

Within sexual harassment and coercion, one in 10 (10.2%) participants reported pressuring someone for dates or sex since the age of 18. One in 20 (6%) reported using emotional or psychological manipulation to get someone to participate in sexual activity (for example, telling them they were a prude if they didn’t have sex).

Just over 4% of respondents reported pressuring someone to take drugs or alcohol before requesting sexual activity. Another 4% reported pressuring someone to participate in unprotected sexual activity.

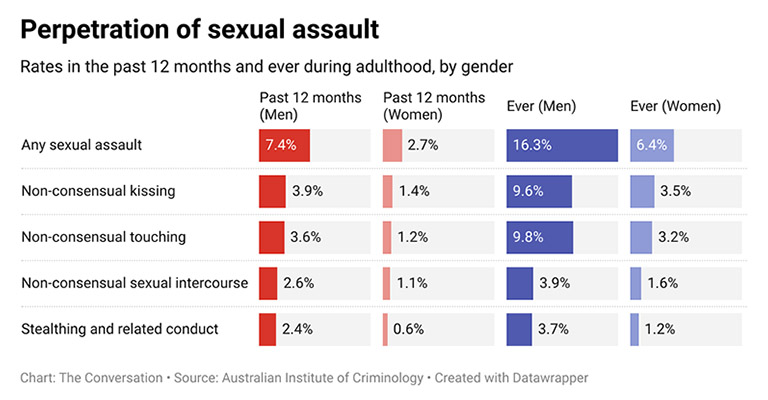

The most common forms of self-reported sexual assault were non-consensual kissing (6.6%) and non-consensual touching (6.4%). Meanwhile, 2.5% of participants reported having perpetrated sexual intercourse without a victim’s consent since the age of 18, while 2.4% said they had perpetrated stealthing (non-consensual removal of a condom during sex) or related behaviours.

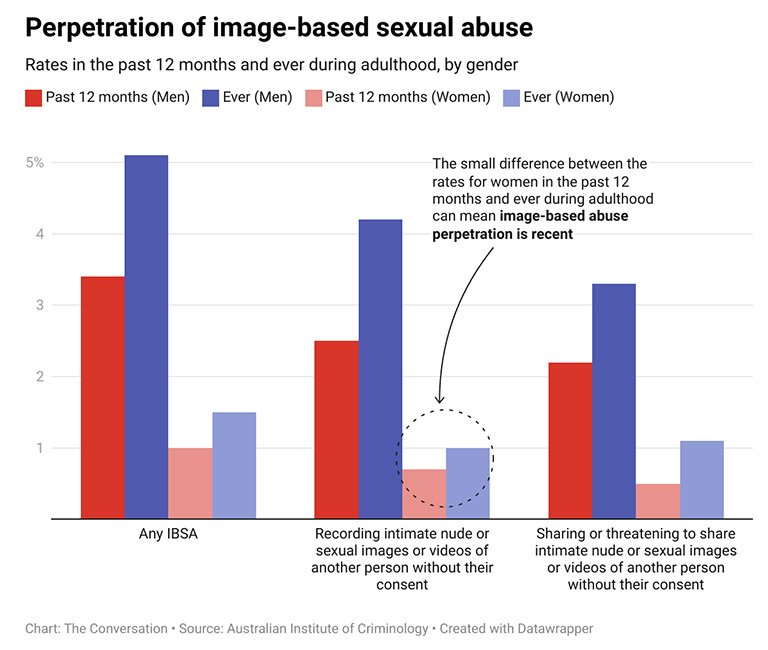

Some 3.3% of participants said they had perpetrated image-based sexual abuse. This was defined as recording, sharing or threatening to share intimate, nude or sexual images or videos of someone else without their consent.

The gendered nature of sexual violence

The study finds the perpetration of sexual violence in Australia is highly gendered. Men were significantly more likely than women to report using all forms of sexual violence, including among perpetrators of multiple forms of these behaviours.

There are specific gender differences that stand out. Men were almost twice as likely to pressure someone into drug and alcohol use before asking for sex. Men were three times as likely as women to have blackmailed someone into sex in the 12 months prior to the survey.

Men were also three times more likely than women to perpetrate image-based sexual abuse. Men were significantly more likely than women to have perpetrated multiple forms of sexual violence.

Aligning with recent calls for a greater focus on serial perpetrators of violence, the study found that among participants who had used any form of sexual violence, 28.9% had used multiple forms since the age of 18.

While these figures are shocking, the report’s authors also warn they are likely to be an underestimate of the true prevalence of sexual violence in Australia. Perhaps unsurprisingly, more than 500 survey participants refused to provide information about their use of sexually violent behaviours.

Why focus on perpetrators?

Research shows all forms of sexual violence are under-reported to police. Yet our understanding of perpetration relies almost solely on police and other justice system data.

Until now, our understanding of the nature and extent of sexual violence in Australia has relied on self-reported data from victims.

Latest results from the Personal Safety Survey show one in five adult women and one in 15 adult men have experienced sexual violence since the age of 15. While important, data from victims reveals little about the people who perpetrate sexual violence.

In recent years there have been calls for a greater understanding of who uses domestic, family and sexual violence. Research shows all forms of sexual violence are under-reported to police. Yet our understanding of perpetration relies almost solely on police and other justice system data.

There is a need for significantly improved understanding of who perpetrates sexual violence. This will inform effective responses, early intervention and prevention initiatives. This research partly addresses this gap.

What is needed now?

Perpetrator research is a difficult undertaking, particularly when asking about behaviours such as domestic, family and sexual violence.

Social desirability bias means people may be unwilling to answer such questions truthfully for fear of making themselves look bad. Perpetrators can also deny or minimise their behaviours.

This study represents a step forward in furthering our understanding of sexual violence perpetration in Australia. However, we still need more detailed insights.

But we cannot effectively respond to and prevent what we do not measure. Sexual violence prevention programs and perpetrator interventions must be underpinned by an accurate understanding of the cohort being targeted and the nature of the abusive behaviours being used. This will maximise their likelihood of being effective in preventing future harm.

This study represents a step forward in furthering our understanding of sexual violence perpetration in Australia. However, we still need more detailed insights.

We need a better understanding of the characteristics of those who engage in multiple forms of sexual violence. We also need research on the nature of sexual violence within under-researched communities such as LGBTQIA+ and culturally and linguistically diverse communities.

This is crucial for informing the current and future work of federal, state and territory governments in developing effective interventions for people who use sexual violence.

This article first appeared on the Conversation, and is republished under a Creative Commons Licence; you can read the original here.

About the Authors

Dr Kate Fitz-Gibbon is a Professor (Practice) in Leadership and Executive Education (LEE) in the Faculty of Business and Economics at Monash University, and an Honorary Professorial Fellow in the Melbourne Law School at University of Melbourne. She also holds an affiliated research appointment with the School of Law and Social Justice at University of Liverpool (UK). Kate is an international research leader in the area of domestic and family violence, femicide, responses to all forms of violence against women and children, perpetrator interventions, and the impacts of law reform in Australia and internationally.

Dr Kate Fitz-Gibbon is a Professor (Practice) in Leadership and Executive Education (LEE) in the Faculty of Business and Economics at Monash University, and an Honorary Professorial Fellow in the Melbourne Law School at University of Melbourne. She also holds an affiliated research appointment with the School of Law and Social Justice at University of Liverpool (UK). Kate is an international research leader in the area of domestic and family violence, femicide, responses to all forms of violence against women and children, perpetrator interventions, and the impacts of law reform in Australia and internationally.

Dr Hayley Boxall is a Research Fellow with the Australian National University who has been undertaking research on domestic and family violence (DFV) and sexual violence for over 10 years. She has published extensively on these topics, with a primary focus on pathways/trajectories into DFV offending and intimate partner femicide, offending and reoffending patterns of DFV perpetrators, and DFV desistance processes. Prior to joining the ANU, Hayley was the Manager of the Australian Institute of Criminology’s Violence against Women and Children Research Program.

Dr Hayley Boxall is a Research Fellow with the Australian National University who has been undertaking research on domestic and family violence (DFV) and sexual violence for over 10 years. She has published extensively on these topics, with a primary focus on pathways/trajectories into DFV offending and intimate partner femicide, offending and reoffending patterns of DFV perpetrators, and DFV desistance processes. Prior to joining the ANU, Hayley was the Manager of the Australian Institute of Criminology’s Violence against Women and Children Research Program.

Picture © fizkes / Shutterstock