Is youth crime actually increasing? Are we at crisis point? It depends on how we define a crisis and what the data says.

In recent months, there has been increasing focus on crime committed by young people in Australia. Politicians are coming under more pressure to respond to these well-publicised criminal acts and the public perceptions that Australia is in the grips of a youth crime crisis.

In Queensland for instance, a group called Voice for Victims has been holding protests and recently met with Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk to push their demands for a stronger law and order response and higher assistance payments to victims.

But is youth crime actually increasing? Are we at crisis point? It depends on how we define a crisis and what the data says.

Today every Queensland daily paper has the same front page calling on the state government and the Opposition to commit to publishing and targeting KPIs experts agree are key to the youth crime problem. All say knee-jerk, band-aid action will not solve this problem. @couriermail pic.twitter.com/PyH05SFxe4

— Stephanie Bennett (@stephconf) February 20, 2023

Youth offending crime data

The minimum age of criminal responsibility is 10 years old in all states and territories, except the Northern Territory which recently raised the age to 12. Young people between the ages of 10 and 13 can only be held criminally responsible, though, if it can be shown they knew what they were doing was seriously wrong.

In Victoria, crime statistics show that from 2014 to 2023, the rate of incidents involving youth offenders has been trending downward (despite some fluctuations). However, from 2021-22 to 2022-23, there was a 24% increase in the rate of incidents committed by youth offenders under the age of 17, per 100,000 of population.

Likewise, data from New South Wales from 2011 to 2022 shows the rate of 10 to 17 year olds being proceeded against by police has also been trending downward. This means the suspected offenders either faced court or a Youth Justice Conference, or received a caution from police.

However, from 2021 to 2022, the rate of young people being proceeded against by police increased by 7%, per 100,000 of population. The rate of those proceeding to court for more serious offences increased by 11% for the same period.

And the 2021-22 Queensland Crime Report showed a 13.7% increase in the number of children aged 10 to 17 being proceeded against by police, compared to the previous year. The total number of youth offenders reached 52,742, the highest number in 10 years.

Queensland premier faces questions about youth crime in a 9 News interview

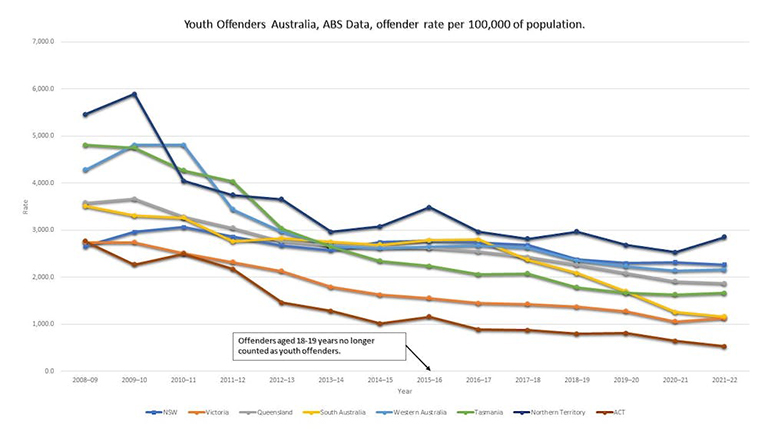

In most of the other states and territories, Statistics data shows the youth offending rates have trended downward over the past decade. From 2020-21 to 2021-22, these rates have either remained steady or decreased in most states and territories. Only the Northern Territory showed a larger increase of 13%.

Youth offenders, principal offence rate per 100,000; ABS data

It should be noted the ABS youth offender rate only counts how many unique offenders came into contact with police – each offender is only counted once, regardless of how many times they may have offended in the period. This means it does not provide an indication of overall recidivism rates by individual young people.

The ABS does, however, provide other data on recidivism. In 2021-22, the proportion of youth offenders proceeded against by police more than once increased in several localities, including Queensland (10%), Tasmania (17%), the NT (5%) and the ACT (8.5%). The other states showed only minor changes from the previous year.

Queensland courts can declare a youth offender a serious repeat offender under the Youth Justice Act. These young people are identified using a special index, which considers a young person’s offending history (including the frequency and seriousness), the time a young person has spent in custody and their age.

In 2021-22 in Queensland, nearly half of all youth offences were committed by serious repeat offenders.

Which offences are showing increases?

In Queensland, the most prevalent offences for young people in 2021-22 included theft, break and enter, and stolen vehicles.

Even though only 18% of all offenders in Queensland were under the age of 18, these youth offenders accounted for more than 50% of all break and enter, robbery and stolen vehicle offenders during the year.

Even though only 18% of all offenders in Queensland were under the age of 18, these youth offenders accounted for more than 50% of all break and enter, robbery and stolen vehicle offenders during the year. For stolen vehicles, the number of youth offenders almost doubled between 2012 and 2022.

In NSW, the most common offences for young people in 2022 were theft, break and enter, and stalking or harassment. Compared to 2021, young people proceeded against by police for thefts had increased by 21% and for break and enters by 55%.

And in Victoria, the most common incidents for youth offenders in 2022-23 were crimes against the person (a 29% increase compared to 2021-2022), property offences (36% increase) and public offences such as public nuisance, and disorderly and offensive conduct (29% increase).

A crisis is a matter of perception

A sense of crisis is created to some degree by not only rising crime rates, but also a sense of helplessness felt by the community and a perceived failing of the Government to provide for a safe and secure community.

How the public perceives crime issues is just as important as the reality of crime trends themselves. The Commonwealth Report on Government Services provides a snapshot of perceptions of safety. In 2021-22, 89% of people felt safe at home at night, while just 32.7% felt safe on public transport and 53.8% on the street.

A survey of Queenslanders showed nearly half of respondents believed youth crime was increasing or at a crisis point. Three-quarters of respondents had taken steps to improve their home security in the last year.

Last week, a survey of Queenslanders showed nearly half of respondents believed youth crime was increasing or at a crisis point. Three-quarters of respondents had taken steps to improve their home security in the last year.

In Queensland, the Government is responding to these concerns with tougher measures. It has controversially proposed using police watchhouses to detain youth offenders, overriding its own Human Rights Act with a special provision only meant to be used in exceptional circumstances.

The Government said this was necessary because the state’s youth detention centres were full and, due to an increase in serious youth offenders, it needed to use police watchhouses to detain them to ensure the community is protected.

Youth justice advocates warn these watchhouses, however, are not suitable places for children, in part, because they could be held with adults and many of the facilities lack exercise yards, natural light and visitor facilities.

Given the recent protests in Queensland, it is reasonable to conclude there is a perception of a crisis in the community over the inability of governments to deal adequately with youth crime, specifically repeat offenders.

While action needs to be taken in the short term to address community safety concerns, all states and territories also need to address the longer-term, multi-factoral causes of youth crime, such as truancy and disengagement from school, drug usage, domestic violence in the home and poor parenting.

This article first appeared on The Conversation, and is republished under a Creative Commons Licence; you can read the original here.

About the Authors

Dr Terry Goldsworthy is an Associate Professor of Criminology at Bond University. He has more than 28 years of policing experience in Australia, achieving the rank of Detective Inspector. Dr Goldsworthy has completed a Bachelor of Commerce, Bachelor of Laws, Advanced Diploma of Investigative Practice and a Diploma of Policing. He was admitted to the bar in the Queensland and Federal Courts as a barrister in 1999. Dr Goldsworthy then completed a Master of Criminology at Bond University, and later completed his PhD focusing on the concept of evil and its relevance from a criminological and sociological viewpoint.

Dr Terry Goldsworthy is an Associate Professor of Criminology at Bond University. He has more than 28 years of policing experience in Australia, achieving the rank of Detective Inspector. Dr Goldsworthy has completed a Bachelor of Commerce, Bachelor of Laws, Advanced Diploma of Investigative Practice and a Diploma of Policing. He was admitted to the bar in the Queensland and Federal Courts as a barrister in 1999. Dr Goldsworthy then completed a Master of Criminology at Bond University, and later completed his PhD focusing on the concept of evil and its relevance from a criminological and sociological viewpoint.

Dr Gaëlle Brotto is Assistant Professor of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Bond University; she has a bachelor of Psychology from the University of Lille 3 in France, and a Masters and PhD of Criminology from Bond University in Australia. Her research interests include victimology, criminal motivations, victim / offender overlap, intimate partner violence, and the utility and application of typologies. Her PhD is the first empirical research directly addressing psychological characteristics associated with the risk of victimisation, particularly female victims of interpersonal violence.

Dr Gaëlle Brotto is Assistant Professor of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Bond University; she has a bachelor of Psychology from the University of Lille 3 in France, and a Masters and PhD of Criminology from Bond University in Australia. Her research interests include victimology, criminal motivations, victim / offender overlap, intimate partner violence, and the utility and application of typologies. Her PhD is the first empirical research directly addressing psychological characteristics associated with the risk of victimisation, particularly female victims of interpersonal violence.

Dr Tyler Cawthray is an Assistant Professor in Criminology and Criminal Justice at Bond University, and has a PhD in Policing and Criminology from Griffith University, and also holds qualifications in International Relations and History. Tyler’s Doctoral Research concluded in 2020 focused on examining the problem of rebuilding the legitimacy of policing institutions in the wake of conflict or significant civil disturbance. His research interests include police legitimacy; police and state building; pacific policing; police ethics, integrity, oversight, and corruption.

Dr Tyler Cawthray is an Assistant Professor in Criminology and Criminal Justice at Bond University, and has a PhD in Policing and Criminology from Griffith University, and also holds qualifications in International Relations and History. Tyler’s Doctoral Research concluded in 2020 focused on examining the problem of rebuilding the legitimacy of policing institutions in the wake of conflict or significant civil disturbance. His research interests include police legitimacy; police and state building; pacific policing; police ethics, integrity, oversight, and corruption.

Picture © M. W. Hunt / Shutterstock