Cyberattacks are on the rise, impacting people, systems, infrastructures and governments with potentially devastating and far-reaching effects. Most recently, these include the massive REvil ransomware attack and the discovery that the Pegasus spyware was tracking more than 1,000 people.

A common cause of cyberattacks involves the exploitation of security vulnerabilities. These are conditions or behaviours that can enable the breach, misuse and manipulation of data. Examples can include poorly written computer code or something as simple as failing to install a security patch.

Exploiting vulnerabilities

The massive data breach served as a wake-up call for the US federal government. Barack Obama’s administration consequently announced the Department of Defense would be responsible for storing federal employee data.

There can be particularly significant impacts when attackers exploit security vulnerabilities involving digital systems used by federal governments.

For example, in July 2015, the United States Office of Personnel Management announced that malicious hackers had exfiltrated highly sensitive personal information and fingerprints of roughly 21.5 million federal workers and their associates, due to a string of poor security practices and system vulnerabilities.

The massive data breach served as a wake-up call for the US federal government. Barack Obama’s administration consequently announced the Department of Defense would be responsible for storing federal employee data.

Not long after that, the ‘Hack the Pentagon’ pilot program was announced, where the US Government invited external experts to responsibly report security flaws. This pilot paved the way for what has become a standard security practice used by the US Government. Since 2020, all American federal agencies have been required to enable the disclosure of security vulnerabilities.

Canada lagging behind

By comparison, our recent report found that the Government of Canada is lagging behind countries like the US by failing to welcome vulnerability reports from external experts.

We haven’t had an attack the size of the Office of Personnel Management breach in the US, but we aren’t immune either. Consider the Equifax breach in 2017, when 19,000 Canadians were affected when attackers exploited a security vulnerability in an online customer portal.

In August 2020, the Canada Revenue Agency locked more than 5,000 user accounts due to cyberattacks partially enabled by the Agency’s lack of two-factor authentication.

Our report, published through the Cybersecure Policy Exchange at Ryerson University, is the first publicly available research that examines how Canada treats the reporting of security flaws in comparison to other countries.

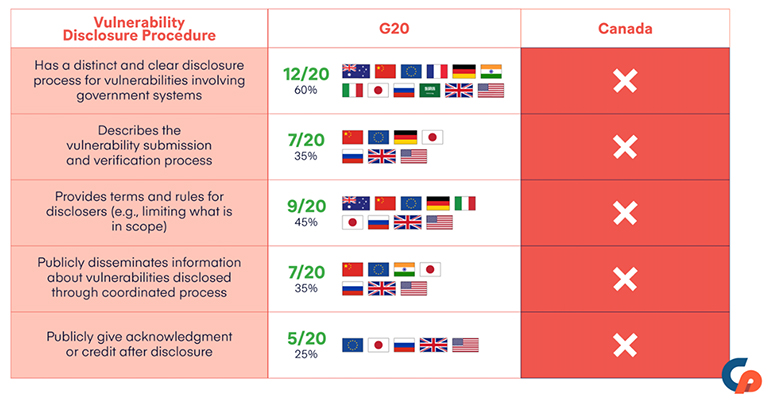

We discovered that while 60% of G20 members have distinct and clear processes for reporting security vulnerabilities in public infrastructure, Canada does not.

When assessing whether the Government of Canada meets standards for vulnerability disclosure in comparison to G20 members, we discovered that Canada is falling behind its peers (Cybersecure Policy Exchange, Ryerson University), Author provided.

Cybersecurity experts can disclose ‘cyber incidents’ to the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security. But this term is defined so narrowly that it excludes vulnerabilities that have not yet been weaponized.

And while the United Kingdom and the US governments have promised to make efforts to fix security flaws that are reported, the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security has made no such promise.

By not supporting and protecting security researchers in identifying vulnerabilities, these gaps ultimately put Canada and Canadians at greater risk.

Vulnerable systems, vulnerable people

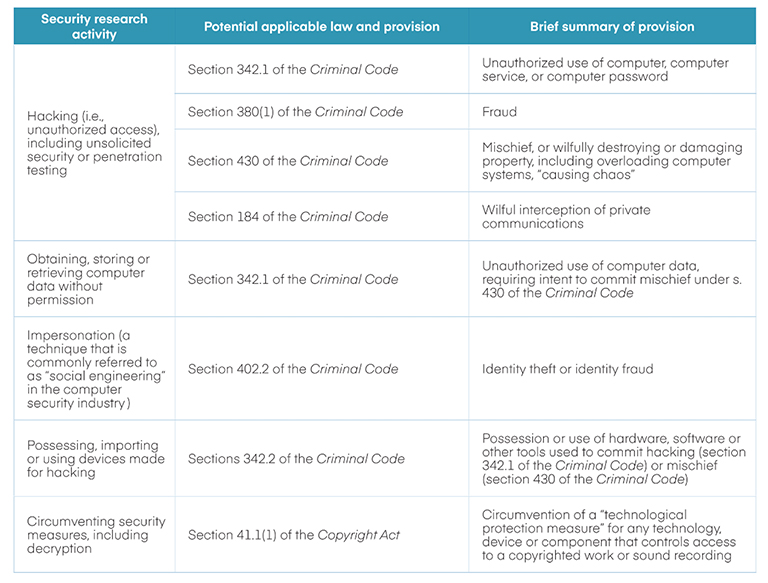

Cybersecurity experts can face significant legal risks when they report security flaws to the Canadian Government. Computer hacking is prohibited by the Criminal Code, and in certain circumstances by laws like the Copyright Act.

Some of the legal risks in Canada for discovering and disclosing security vulnerabilities found in software and hardware, (Cybersecure Policy Exchange, Ryerson University), Author provided.

But unlike in the Netherlands and the US, there is no legal framework here for reporting security vulnerabilities in good faith.

Canada’s current approach has a chilling effect on the disclosure of security weaknesses found not only in government systems, but also for all software and hardware. This approach largely leaves cybersecurity researchers in the dark about whether – and how – they should notify the Government when they spot security flaws that could be exploited.

A cybersecure Canada requires working with experts who identify the security risks faced by our institutions and infrastructure. It’s not too late for the federal government to institute a process allowing experts to report security flaws, and to draw on best practices while doing so.

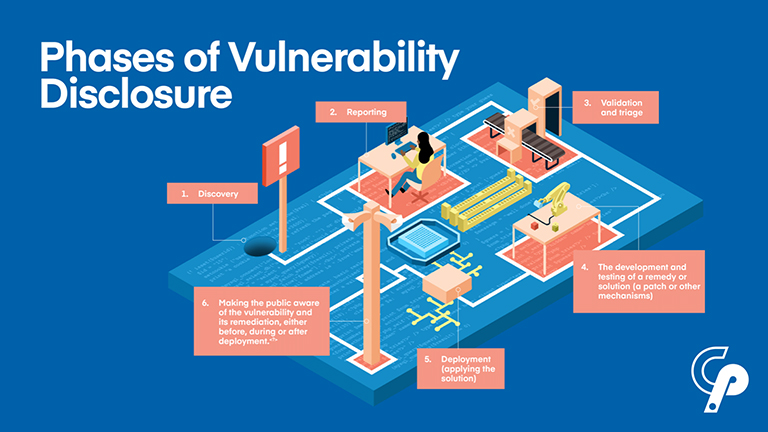

Our work outlines the importance of defining who can submit vulnerability reports, and describes what the reporting and fixing process can look like. It’s important to credit or recognize the experts who disclosed. The public should be given information about vulnerabilities and the solutions required to fix them.

The phases of vulnerability disclosure: discovery, reporting, validation and triage, developing a solution, applying that solution, and informing the public (Cybersecure Policy Exchange, Ryerson University), Author provided.

Imperative improvements

Cybersecurity experts are “a significant but underappreciated resource” when it comes to reducing security risks of government systems. They want to help.

The Canadian Government needs to implement clearer processes and policies to foster co-operation with cybersecurity experts working in the public interest.

As cyberattacks grow in frequency, scale and sophistication, better cybersecurity practices in Canada are not just desirable — they are imperative.

About the authors

Yuan Stevens is a legal and policy expert focused on information security and data protection rights, bringing years of international experience to her role at the Ryerson Leadership Lab as Policy Lead on Technology, Cybersecurity and Democracy, having examined the impacts of technology on vulnerable populations in Canada, the US, and Germany. She is a research affiliate at Data & Society Research Institute and the Centre for Media, Technology & Democracy at McGill University.

Yuan Stevens is a legal and policy expert focused on information security and data protection rights, bringing years of international experience to her role at the Ryerson Leadership Lab as Policy Lead on Technology, Cybersecurity and Democracy, having examined the impacts of technology on vulnerable populations in Canada, the US, and Germany. She is a research affiliate at Data & Society Research Institute and the Centre for Media, Technology & Democracy at McGill University.

Stephanie Tran is a researcher and policy analyst examining public policy and human rights issues related to digital technologies at the Ryerson Leadership Lab, and has contributed research and policy analysis at the Cybersecure Policy Exchange, Citizen Lab, Amnesty International Canada, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, and more. She holds a dual degree Master of Public Policy from Sciences Po in Paris, and a Master of Global Affairs from the University of Toronto.

Stephanie Tran is a researcher and policy analyst examining public policy and human rights issues related to digital technologies at the Ryerson Leadership Lab, and has contributed research and policy analysis at the Cybersecure Policy Exchange, Citizen Lab, Amnesty International Canada, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, and more. She holds a dual degree Master of Public Policy from Sciences Po in Paris, and a Master of Global Affairs from the University of Toronto.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article here.