During a recent visit to Fiji, I heard firsthand the poor state of public health messaging in response to the recent uptick in drug use.

But some crucial areas of need are being overlooked: addressing the impacts of drug use in correctional facilities, for example, and increasing harm reduction and healthcare services to address the dual epidemic of meth use and HIV/AIDS.

In a local market in Labasa, on the island of Vanua Levu, a voice came over the loudspeaker warning people not to use “meth”. The female voice warned that using meth “will make you go crazy”, “lose your family” and other dire consequences of a similar tone.

Raising awareness of the risks associated with drug use is critical. But fear-based messaging can amplify feelings of shame and stigmatisation. These types of warnings can contribute to people being shunned by their communities, making attempted access to the few treatment options available more challenging.

Remarking on the announcements to our escort, we met with the woman behind the microphone. She was a police officer, so we were keen to ask about what training she had, if any. Unfortunately, she had little time for conversation. The demands of the job are relentless.

The Pacific, and especially Fiji, has gained significant attention in recent years as both a transit route for drug trafficking and destination. A Lowy Institute report by Jose Sousa-Santos highlighted that Pacific countries are a “casualty of the criminal greed of organised crime and the drug appetite of Australia and New Zealand”.

The Pacific Policing Initiative is one avenue through which Australia is responding to drug trafficking issues, and the government has also built Australia-based infrastructure for training Pacific police.

But some crucial areas of need are being overlooked: addressing the impacts of drug use in correctional facilities, for example, and increasing harm reduction and healthcare services to address the dual epidemic of meth use and HIV/AIDS.

As an example, in 2024, Fiji reported a 573% increase in HIV infections since 2017, predominantly among men and driven by injecting drug use and transmission to their sexual partners.

This increase places Fiji among a small number of nations with rising HIV infections amid decades of global efforts and investment that has seen HIV rates decrease considerably. The increase shows how drugs and the consequences of use pose a risk to the economic prosperity for the Pacific.

Problematic male drug use

There are potential lessons to be drawn from other small island states exploited as drug transit hubs.

The impact of drug use on men and their ability to work became clear. Instead of identifying barriers for women’s participation in the law enforcement sector, many women officers told us that it is the men who need help.

The Seychelles in Eastern Africa, on the other side of the Indo-Pacific region, has a decades-long drug problem, formerly largely heroin, now increasingly meth. It is estimated that approximately 10% of Seychellois experience drug-related issues.

Seychelles shares some similarities with Pacific Islands, such as being tourism dependent and with young people and the working population seeking better education or economic opportunities abroad.

Interviews colleagues and I conducted for research on gender and policing in Seychelles identified a unique and unexpected phenomenon. Initially, we were positively surprised that the share of women in policing is almost 47% – possibly the highest in the world.

However, explanations as to how this important feat was achieved reveal that it may have less to do with particular organisational initiatives, but rather that it reflects the composition of the available working population.

The impact of drug use on men and their ability to work became clear. Instead of identifying barriers for women’s participation in the law enforcement sector, many women officers told us that it is the men who need help.

The impact of Seychelles being used as a drug transit route had contributed to higher rates of problematic drug use among men, affecting their ability to work (and driving up rates of domestic violence).

Alarm bells for the Pacific Islands

We were told that men were experiencing difficulties holding down stable jobs with a regular salary, in favour of informal or short-term labour, more likely to pay cash or a daily rate, which would serve their recreational or drug use needs better.

Rather than continue with recruiting a 50-50 split of women and men to the police academy, the Seychelles Police Force essentially introduced an affirmative action initiative for men in the form of selecting a higher percentage than women to undertake training, to accommodate for the higher rates of male attrition that would follow.

We were told that men were experiencing difficulties holding down stable jobs with a regular salary, in favour of informal or short-term labour, more likely to pay cash or a daily rate, which would serve their recreational or drug use needs better.

Consequently, several months of disciplined training at the police academy is too challenging for a higher proportion of men.

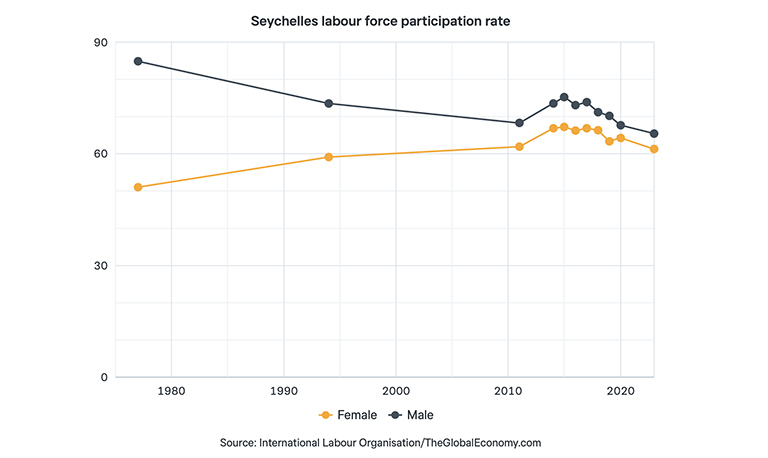

To triangulate this data, labour force participation rates support the downward trend among men over recent decades and an upward trend among women, to the extent that labour force participation is near equal (65% male, 61% female in 2023).

There appears to be a positive impact on gender equality in policing in that women are advancing to higher ranks, and thus, normalising women in leadership, especially among male counterparts and the community, and providing more role models to junior women. Nonetheless, the downward trend in male labour force participation needs to be addressed lest it continue to plummet.

The Seychelles experience as a drug transit hub should ring alarm bells for the Pacific Islands.

If Australia and New Zealand want to support a peaceful, prosperous and resilient Pacific region, funding for law enforcement and criminal justice initiatives should include public health policing approaches.

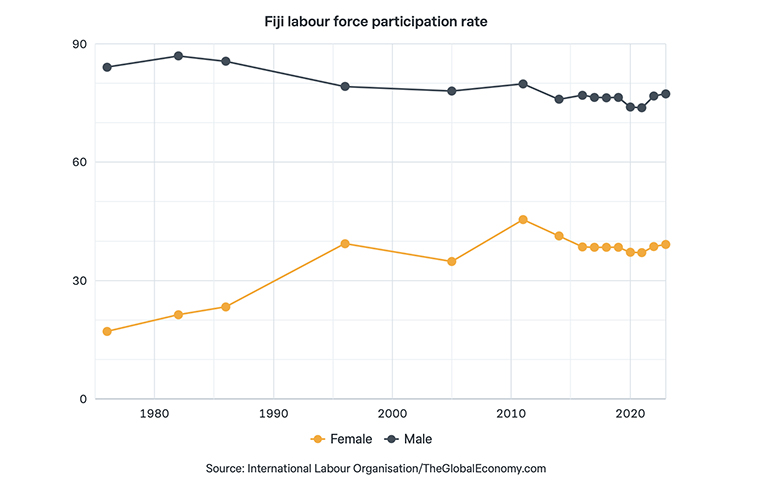

In 2023, labour force participation in Fiji was 77% among men and 39% among women. If evidence-based, public health approaches to drug use, prevention, treatment and rehabilitation are relegated to the bottom of donor funding priorities, efforts to stem organised crime and drug trafficking may cast a long shadow over prospects for economic development in decades to come.

Echoing the conclusions reached by Santos-Sousa, the Pacific Islands are collateral damage in Australia (and New Zealand’s) appetite for illicit drugs.

If Australia and New Zealand want to support a peaceful, prosperous and resilient Pacific region, funding for law enforcement and criminal justice initiatives should include public health policing approaches to ensure there is a strong and capable workforce by 2050 to achieve these goals.

This article first appeared in The Interpreter, published by The Lowy Institute, and is republished with the author’s permission; you can read the original here.

Picture: Police officer at Labassa market in Fiji (© Dr Melissa Jardine)