The legitimacy of legal authorities is recognised globally as crucial for the state’s ability to function in a justifiable and effective manner. This applies, in particular, to the police.

The data shows that public trust in the police has been low throughout most of the democratic period. Between 2020 and 2021, however, there was significant drop in the level of trust ordinary people had in the police.

Recently, South Africa’s Defence Minister Thandi Modise lamented the low level of public trust in law enforcement agencies in the country. In particular, the minister, who also heads the country’s Justice, Crime Prevention and Security Cluster, drew attention to a persisting legitimacy problem in the relationship between the police and the public.

To provide further context to the extent and nature of this challenge, we examined representative survey data on trends in police confidence since the late 1990s. The data shows that public trust in the police has been low throughout most of the democratic period. Between 2020 and 2021, however, there was significant drop in the level of trust ordinary people had in the police.

Our research outlines some of the drivers of general attitudes towards the law enforcement. We hope that this work will be used to design interventions to restore the public’s faith in the police.

Tracking confidence in the police

Views on crime and policing in the country have been a thematic priority in the South African Social Attitudes Survey series since its inception in 2003.

This series is conducted annually by the Human Sciences Research Council using face-to-face interviews, and has been designed to be nationally representative of the adult population aged 16 years and above.

Each year, between 2,500 and 3,200 people are interviewed countrywide. The data are weighted using Statistics South Africa’s most recent mid-year population estimates.

The survey series builds on earlier representative public opinion surveying at the Council, known as the Evaluation of Public Opinion Programme series. On certain topics (such as policing) this allows us to extend the period of analysis back to before the early 2000s.

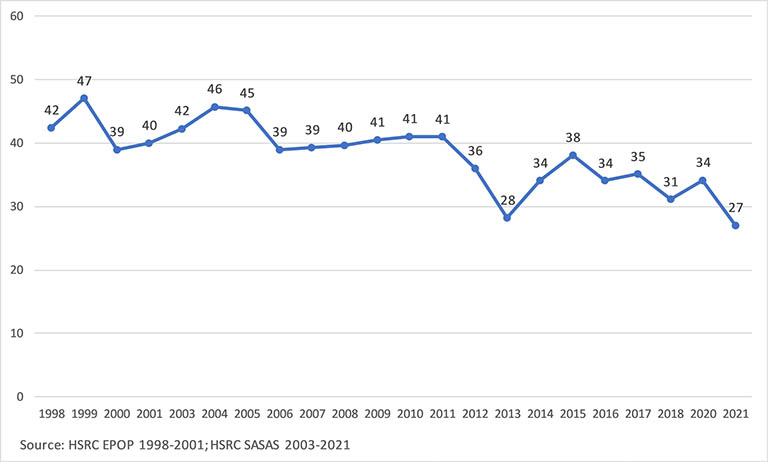

The pattern of public confidence in the police over the 1998 to 2021 period is presented in Figure 1. Trust levels have remained relatively low over this period. Not once during this 23-year interval did more than half the adult public say that they trusted the police. It would seem that the issue of low trust in the police is not new.

Figure 1: Confidence in the police, 1998-2021 (% trust/ strongly trust) HSRC EPOP 1998-2001; HSRC SASAS 2003-2021

Between 1998 to 2010, the average level of trust in the police was relatively static. It ranged between 39% and 42% in all but a few years.

This was followed by a sharp decline between 2011 and 2013, following the killing by police of 34 striking miners at Marikana, North West Province, in August 2012. But confidence had almost returned to the 2011 level by 2015.

The 2016 to 2020 period was characterised by modest fluctuation between 31% and 35%. The hard COVID-19 lockdown imposed by the state in 2020 saw instances of police brutality. However, we did not observe a decline in public confidence in the police during the 2020 period.

In 2021 public trust in the police dipped to a low 27%. This appears to be linked to the July 2021 social unrest. Many have criticised the police for poor performance of during the unrest.

Substantial provincial variation in trust in the police underlies this national trend (Table 1). Looking at the 2011-2021 period, we find that adults in the Western Cape, Limpopo and Gauteng provinces have consistently reported lower levels of trust in the police than the national average. The country has nine provinces.

The distinct decline in trust observed between 2020 and 2021 was unevenly reflected across provinces. The largest decline was in the Western Cape. It fell more than 20 percentage points, greatly exceeding the national decline of 7 percentage points.

This may reflect a failure to rein in gangsterism in that province. More moderate (but still sizeable) declines were identified in Limpopo, Northern Cape, and Gauteng.

Table 1: Provincial trends in police confidence, 2011-2021 (% trust / strongly trust) HSRC SASAS 2011-2021

Factors affecting confidence in the police

Based on the survey evidence, various factors influence public trust in, and legitimacy of, the police in South Africa. These are briefly summarised below.

Importantly, public confidence in democratic institutions has shown a strong downward trend over the past 15 years. This has had a bearing on confidence in the police.

- Experiences of crime: Those who had been recent victims of crime displayed significantly lower levels of trust in the police.

- Fear of crime: Higher levels of fear are associated with lower trust in the police. This applies to classic measures such as fear of walking alone in one’s area after dark, as well as worrying about home robbery or violent assault. These associations have been found across multiple rounds of surveying.

- Experiences of policing: Negative experiences with police have a bearing on how the public judge police. Those reporting unsatisfactory personal contact with police officers expressed lower trust levels than those reporting satisfactory contact.

- Well-publicised instances of police abuse or failure: These can also reduce public confidence in police. Apart from the 2012 Marikana massacre, another prominent example is the perceived ineffectiveness of the police in responding to the July 2021 social unrest.

- Perceptions of police corruption: These have a strong, negative effect on confidence in police.

- Perceived fairness and effectiveness: Past in-depth research has shown that the South African public strongly emphasises both fairness and effectiveness as important elements in their overall assessments of confidence in police. The more the police are seen to be acting unfairly on the basis of race, class or other attributes, the more people are likely to view them as untrustworthy.

Similarly, perceptions that the police treat people disrespectfully, lack impartiality in their decision making, or transparency in their actions, can also undermine public confidence. If the police are seen as ineffective in preventing, reducing and responding to crime, this will also diminish confidence.

Another factor influencing how the public view the police is the broader evaluation of the government’s democratic performance and trustworthiness. Importantly, public confidence in democratic institutions has shown a strong downward trend over the past 15 years. This has had a bearing on confidence in the police.

Polishing the tarnished badge

Low and diminishing confidence in the police, if left unchecked, will continue to undermine police legitimacy in South Africa. Recent recommendations put forward by the Institute of Security Studies could improve public attitudes towards the police.

They include dispensing with an excessively hierarchical police culture, promoting competent and ethical police leadership, as well as strengthening other parts of the overall system of police governance.

Key also is the implementation of a non-militaristic policing ethos. This should be framed around a service culture and use of minimal force. It also requires police to put more measures in place to monitor and control the use of force, and promote a culture of police accountability.

These ideas warrant serious attention. They matter fundamentally for preventing further instances of police misuse of force, corruption among senior officials, and police ineffectiveness in handling crime. This is crucial for stemming and reversing the eroding confidence in the badge.

About the Authors

Dr Benjamin Roberts is Acting Strategic Lead and Research Director in the Developmental, Capable and Ethical State (DCES) research division of South Africa’s Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC). He has been co-ordinating the annually conducted, nationally representative South African Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS) series since its inception in 2003. He has a BSc Town and Regional Planning (Wits), an MSc Urban and Regional Planning (Development)(Natal) and a PhD Social Policy and Labour Studies (Rhodes University).

Dr Benjamin Roberts is Acting Strategic Lead and Research Director in the Developmental, Capable and Ethical State (DCES) research division of South Africa’s Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC). He has been co-ordinating the annually conducted, nationally representative South African Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS) series since its inception in 2003. He has a BSc Town and Regional Planning (Wits), an MSc Urban and Regional Planning (Development)(Natal) and a PhD Social Policy and Labour Studies (Rhodes University).

Dr Steven Gordon is a Senior Research Specialist in the Developmental, Capable and Ethical State (DCES) research division of the HSRC, and is a member of the SASAS unit. He has a Doctorate in Philosophy from the University of KwaZulu-Natal. An experienced researcher, for the last five years his main academic interested has been public attitudes towards international migration; most recently he has been investigating public attitudes towards anti-immigrant hate crime in South Africa.

Dr Steven Gordon is a Senior Research Specialist in the Developmental, Capable and Ethical State (DCES) research division of the HSRC, and is a member of the SASAS unit. He has a Doctorate in Philosophy from the University of KwaZulu-Natal. An experienced researcher, for the last five years his main academic interested has been public attitudes towards international migration; most recently he has been investigating public attitudes towards anti-immigrant hate crime in South Africa.

This article first appeared on The Conversation, and is republished under a Creative Commons Licence. The original can be read here.

Picture © Jaxons / iStockphoto

My personal knowledge of policing in South Africa is now dated, that caveat aside now.

Policing in South Africa, whether under apartheid and the new nation, has always been unpopular, if not hated – right across all communities. They are seen as brutal, corrupt, dangerous, ineffective and violent. Add to this mix a long history of political intervention, direction and the like – with an elected ANC government controlling the police service.

Given the powerful “drivers” for the level of crime and violence which occurs every day, not just in the headline instances it is serious fault that the authors have no options for addressing them here.