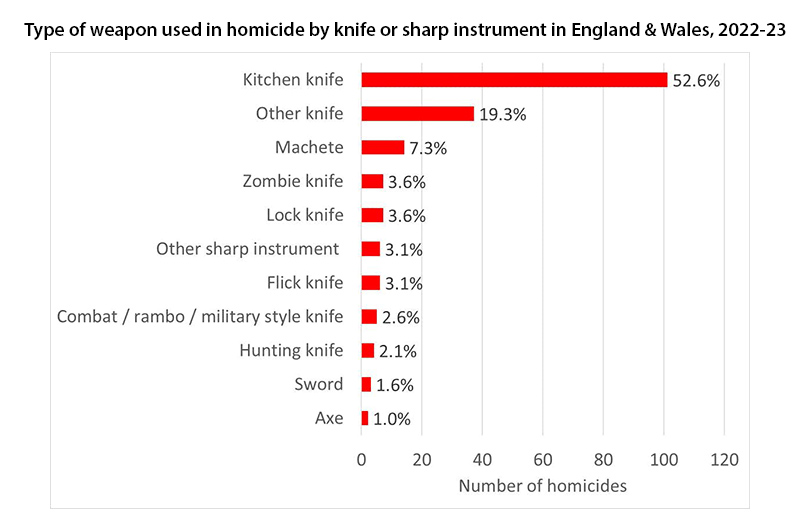

In England and Wales in the last year, pointed kitchen knives were used in more than half of murders where the type of knife was known, compared with 4% for zombie knives.

Think about the last time you used a knife when eating. The round-tip table knife is the default at breakfast, lunch and dinner, both at home and in restaurants.

The reason the tip is rounded is to reduce the potential for harm from violence or other injury. It is such a mundane part of everyday life that we barely notice its role in crime prevention.

Knives are the murder weapon of choice in the UK. And despite sensational headlines about zombie knives and machetes, the most popular knife by far for murder in is the pointed kitchen knife.

In England and Wales in the last year, it was used in more than half of murders where the type of knife was known, compared with 4% for zombie knives.

Data via ONS 2024. Author provided, CC BY

In a new paper published in the journal Crime Science, we propose that the round-tip default needs to be extended to kitchen knives. Not only would the murder rate fall but so too would knife crime generally. And it would also prevent tens of thousands of non-criminal knife injuries at work and in the home. So, we propose phasing pointed-tip knives out over a number of years.

The pointed tip of a kitchen knife is what makes it an attractive, effective murder weapon. Research comparing the harm from stabbing by different knife types (including pointed, round-tip, and serrated or not) found – perhaps not surprisingly – pointed straight-edge knives and pointed serrated knives to be very damaging, while round-tip knives do little or no damage.

There has been significant progress in control of lethal knives in the UK. The Offensive Weapons Act of 2019 made it illegal to possess certain kinds of dangerous knife (such as flick knives) even in private, and banned carrying kitchen knives in public without good reason. In September 2024, it became illegal to possess or sell zombie-style knives and machetes.

Phasing out pointed-tip kitchen knives, to be replaced by round-tip knives, is a natural extension of this progress and, we argue, would significantly reduce deaths and injuries.

Evidence-based knife crime policy

Knife crime in England and Wales increased in the 2010s, according to police crime records, hospital admissions, and knife-related homicides. Each almost doubled from 2012-18, before levelling off or declining slightly since then.

Existing anti-knife crime policies are limited at best, with neither various policing efforts nor Violence Reduction Units (in 18 problem areas since 2019) yet to prove effective.

Existing anti-knife crime policies are limited at best, with neither various policing efforts nor Violence Reduction Units (in 18 problem areas since 2019) yet to prove effective.

The one thing we know to be effective is weapons control policy, as a way to reduce opportunities for crime. This is clearest in the contrast between gun-related homicides in the US and UK: rates in the US, where policy is based on an unfortunate constitutional right to carry a gun, are dozens of times higher.

Is it feasible to expect knives to change in every kitchen? A few years ago, many readers would have baulked at the notion that fossil-fuelled vehicles could be phased out – a process now well underway in the UK and elsewhere, which provides a model for our proposal of phasing out pointed kitchen knives.

Such a change won’t happen overnight, of course, and we propose phases across a number of years – perhaps a decade or longer. An initial consultation period is needed, plus marketing to promote knowledge, purchasing and use of safer knives.

Some natural wastage will help, as old knives are replaced by safer ones over time, and time is also needed for manufacturers to adjust.

Incentives and exceptions may be required. Several years of gentle encouragement may be needed for us to get used to the idea. Over time, this can shift to stronger incentives with the ultimate goal of a full ban on pointed-tip knives – that is, the same model we are using for fossil-fuel vehicles.

The manufacturer Viners has created a line of round-tip knives. Viners, CC BY

Some potential criticisms are non-starters. First, there are no culinary drawbacks to round-tip knives, according to cutlery manufacturer Viners, which developed its line of safety knives with the input of 1,700 people.

Killer kitchen knives should be phased out as dangerous and unnecessary… Knife crime in general, and knife carrying, will decline if the nation’s weapon of choice is no longer available.

Second, few offenders would switch to other weapons. Screwdrivers, scissors and other items are less numerous, less available and make inferior weapons. Screwdrivers may be in a garage, shed or elsewhere. The design of scissors does not facilitate stabbing and makes them unwieldy.

Bottles are a possibility, but containers at home tend to be plastic or cardboard, and most beer is in cans. Many beer bottles are too large (750ml) or too small (330ml stubbies), plus it takes skill or luck to weaponise a bottle.

This practice of switching weapons is more formally known as “tactical displacement”, and there is extensive theory and evidence showing it is the exception, not the rule, among perpetrators.

Killer kitchen knives should be phased out as dangerous and unnecessary. Round-tip knives are less likely to tempt violence, and less damaging if used. Knife crime in general, and knife carrying, will decline if the nation’s weapon of choice is no longer available.

This article first appeared in The Conversation, and is republished under a Creative Commons Licence; you can read the original here.

About the Authors

Graham Farrell is Professor of Crime Science at the University of Leeds, having previously been a professor at universities in Canada (Simon Fraser) the US (Rutgers, Cincinnati), and Loughborough University, and deputy research director at the Police Foundation, Washington DC. His earlier career included working as an international civil servant at the UN in Vienna, Research Associate at the Centre for Criminological Research at Oxford University, and research assistant at the Home Office. His research interests are in crime science (particularly situational crime prevention) with a current focus on the international crime drop.

Graham Farrell is Professor of Crime Science at the University of Leeds, having previously been a professor at universities in Canada (Simon Fraser) the US (Rutgers, Cincinnati), and Loughborough University, and deputy research director at the Police Foundation, Washington DC. His earlier career included working as an international civil servant at the UN in Vienna, Research Associate at the Centre for Criminological Research at Oxford University, and research assistant at the Home Office. His research interests are in crime science (particularly situational crime prevention) with a current focus on the international crime drop.

Dr Toby Davies is Associate Professor in Criminal Justice Data Analytics at the University of Leeds. A quantitative criminologist with interest in spatial analysis, networks and computational methods, he completed his Doctorate at UCL and spent three years as a research associate on the Crime, Policing and Citizenship project, before becoming a Lecturer and Associate Professor in 2021; he joined Leeds in 2023. Toby has worked with the West Yorkshire, Thames Valley and West Midlands forces, and has provided analysis to other agencies including the London Mayor’s Office for Policing & Crime and the UK Home Office.

Dr Toby Davies is Associate Professor in Criminal Justice Data Analytics at the University of Leeds. A quantitative criminologist with interest in spatial analysis, networks and computational methods, he completed his Doctorate at UCL and spent three years as a research associate on the Crime, Policing and Citizenship project, before becoming a Lecturer and Associate Professor in 2021; he joined Leeds in 2023. Toby has worked with the West Yorkshire, Thames Valley and West Midlands forces, and has provided analysis to other agencies including the London Mayor’s Office for Policing & Crime and the UK Home Office.

Picture © VITALII BORKOVSKYI / Shutterstock

It’s surprising that this article has not attracted positive comment already.

Proposals to increase police effectiveness, whether in relation to crime reduction or more latterly, public confidence often use soft and aspirational chains of logic.

This one is straightforward in principle. Take pointed knifes out of circulation – or at least stop producing and importing them – and you will have fewer stabbings over time.

Often the simplest ideas are the best ones and hopefully this one will gain traction.