Crime prevention efforts need to start earlier and be tailored to the experiences of those most at risk.

A major Australian study tracking more than 80,000 Queenslanders from birth to adulthood reveals stark differences between men and women in patterns of criminal behaviour. These patterns offer insights into effective crime prevention strategies.

Our findings point to a clear takeaway: most people will never seriously come into contact with the criminal justice system. But for the small proportion who do, their paths into crime are shaped early and differently for men and women.

That means crime prevention efforts need to start earlier and be tailored to the experiences of those most at risk.

A rare opportunity

Our research followed more than 83,000 people born in Queensland in 1983 and 1984, and linked their early life records with official police data to understand who offended and how their patterns changed over time.

Few studies worldwide have followed such a large population from childhood through to early adulthood. This gave us a unique opportunity to examine not just if people committed crime, but when, how often, and the types and seriousness of their offences.

Most people don’t offend, but some do – repeatedly

The clearest finding was also the most reassuring: the vast majority of people never commit serious offences. That means efforts to prevent crime can be more precisely targeted, ensuring interventions focus on a smaller, high-risk group rather than the general population.

Most women fell into the low or non-offending groups. Only a small proportion followed a pattern of serious or repeat offending.

Non-offending was most prevalent, but five distinct offending groups for both men and women were identified.

Among men, these ranged from those who rarely offended to a small group that started early and continued into adulthood, and another that mostly offended during adolescence but later stopped.

In contrast, most women fell into the low or non-offending groups. Only a small proportion followed a pattern of serious or repeat offending.

These trajectories were categorised as follows:

Women:

- non-offending: 79.9%

- adolescent-limited low: 8.5%

- adult-onset low: 8.6%

- early adult-onset escalating: 1.3%

- early onset young adult peak: 1.4%

- chronic early adult peak: 0.4%

Men:

- non-offending: 54.4%

- low: 31.0%

- early adult-onset low: 6.5%

- early onset young adult peak: 4.8%

- chronic adolescent-onset: 2.2%

- chronic early adult peak: 1.1%

Among the women who did offend, there were notable differences compared to men – not just in frequency but in the types of offences, how often they had contact with police, and their experience with youth detention.

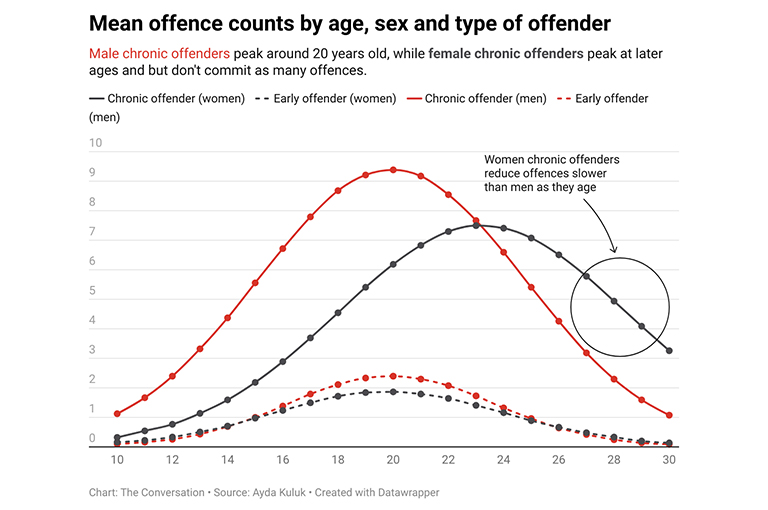

Patterns differ by sex

For boys and young men, those in the persistent offending group had earlier and more frequent contact with police, were more likely to face serious charges and often experienced youth detention.

These differences suggest sex shapes not just the likelihood of offending, but the nature of offending and how people interact with the justice system.

For girls and young women, fewer entered the system overall but those with repeat contact showed distinct patterns: their offences tended to differ from those of men, with a greater focus on property-related crimes as well as drug and traffic violations, rather than the more frequent violent crimes seen among young men.

While they were less likely to be detained, their level of system contact was higher than that of most men in the low offending group.

These differences suggest sex shapes not just the likelihood of offending, but the nature of offending and how people interact with the justice system.

One-size-fits-all crime prevention won’t work

Our findings suggest a nuanced approach to crime prevention – one that recognises both the gendered nature of offending and the early life experiences that shape it.

For boys and young men, this could mean early identification of behavioural issues, stronger support in schools, and support to create stable, safe home environments.

For girls and young women, more effective interventions might involve trauma-informed care (an approach that acknowledges past trauma and prioritises safety, trust and empowerment), along with tailored mental health support and services focused on recovery.

These gender-sensitive approaches are not just about being fair, they’re about being effective and equitable. When we better understand the roots of offending behaviour, we can design policies that reduce it.

Why early intervention matters

It’s easy to think of crime as something that starts with a police report or a court appearance. But the conditions for offending, or avoiding it, are often set much earlier.

Recognising these patterns gives us a powerful opportunity to design earlier and more targeted prevention. That means fewer people in the justice system and healthier, safer communities for everyone.

Here are two real-life examples: What if we saw a child’s aggression at school not as “bad behaviour” but as a red flag for family violence at home? What if a teenage girl’s shoplifting was a symptom of trauma or mental illness?

This research reinforces the value of early, targeted intervention. That doesn’t just mean more programs, it means smarter programs, ones that focus resources on those most at risk in ways that match their lived experience.

Our study is one of the most comprehensive of its kind in Australia. It confirms that while most people never offend, a small group follow early, distinct pathways into crime.

Recognising these patterns gives us a powerful opportunity to design earlier and more targeted prevention. That means fewer people in the justice system and healthier, safer communities for everyone.

If we want to stop crime before it starts, we need to start early, and we need to pay attention to the very different paths children may be on.

This article first appeared on The Conversation, and is republished under a Creative Commons Licence; you can read the original here.

About the Author

Ayda Kuluk is a PhD Candidate in Criminology and Criminal Justice at Griffith University, whose research specialises in life course and developmental pathways to crime, youth justice, mental health, and alcohol-related violence. She works across qualitative and quantitative methods, with expertise in program evaluation, data management, and statistical analysis. Ayda’s research aims to inform policy and practice through culturally sensitive and evidence-based approaches.

Ayda Kuluk is a PhD Candidate in Criminology and Criminal Justice at Griffith University, whose research specialises in life course and developmental pathways to crime, youth justice, mental health, and alcohol-related violence. She works across qualitative and quantitative methods, with expertise in program evaluation, data management, and statistical analysis. Ayda’s research aims to inform policy and practice through culturally sensitive and evidence-based approaches.

Picture © Alena Lom / Shutterstock