The rescheduled police and crime commissioner (PCC) elections in England and Wales are set to take place in just under a month’s time, on Thursday 6 May 2021. Policing Insight is keeping a close eye on the various contests, with a dedicated channel and a page for each police area being contested.

This latest article takes a look at which PCC posts are likely to be the most closely contested, which ‘safe seats’ seem destined to remain with the incumbent officers or secured by large part majorities, and the potential political diversity of the next cohort of PCCs, should those election predictions materialise.

PCC Election 2021: Click a police area to view candidates and results from previous elections

Avon & Somerset | Bedfordshire| Cambridgeshire | Cheshire | Cleveland | Cumbria | Derbyshire | Devon & Cornwall | Dorset | Durham | Dyfed-Powys | Essex | Gloucestershire | Gwent | Hampshire | Hertfordshire | Humberside | Kent | Lancashire | Leicestershire | Lincolnshire | Merseyside | Norfolk | North Wales | North Yorkshire | Northamptonshire | Northumbria | Nottinghamshire | South Wales | South Yorkshire | Staffordshire | Suffolk | Surrey | Sussex | Thames Valley | Warwickshire | West Mercia | West Midlands | Wiltshire

With 39 to be elected – 35 police and crime commissioners (PCCs), and four police, fire and crime commissioners (PFCCs) – there are 166 confirmed candidates: 39 Conservative, 39 Labour, 39 Liberal Democrat, 11 Reform UK, seven Green, four Plaid Cymru, two English Democrat, one Gwlad, one Propel, one Hampshire Independent, one Lincolnshire Independent, one Zero Tolerance Policing ex-Chief, one candidate for the We Matter Party, and 19 Independents (including one Independent PCC previously elected as an Independent, and one Independent PCC previously elected as a Conservative).

Where are the election results likely to be the tightest, or potentially the most surprising or hard fought? In a previous article focusing on (lack of) diversity of candidates, I mentioned briefly that Bedfordshire was likely to be tightly fought, plus that Surrey promised to provide a fascinating competition.

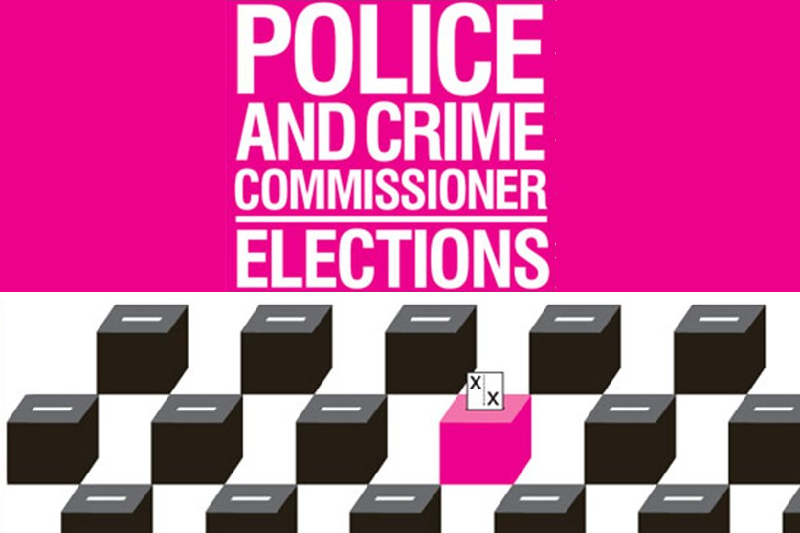

At the last PCC elections in May 2016, Policing Insight presented this analysis of the results. Prior to those 2016 elections, Independent PCCs were far more commonplace, so our ‘swingometer’ contained three primary dimensions – Conservative, Labour and Independent. Broadly, the ‘more marginal’ seats are closer to the centre of the circle and/or closer to one of the interfaces between the segments.

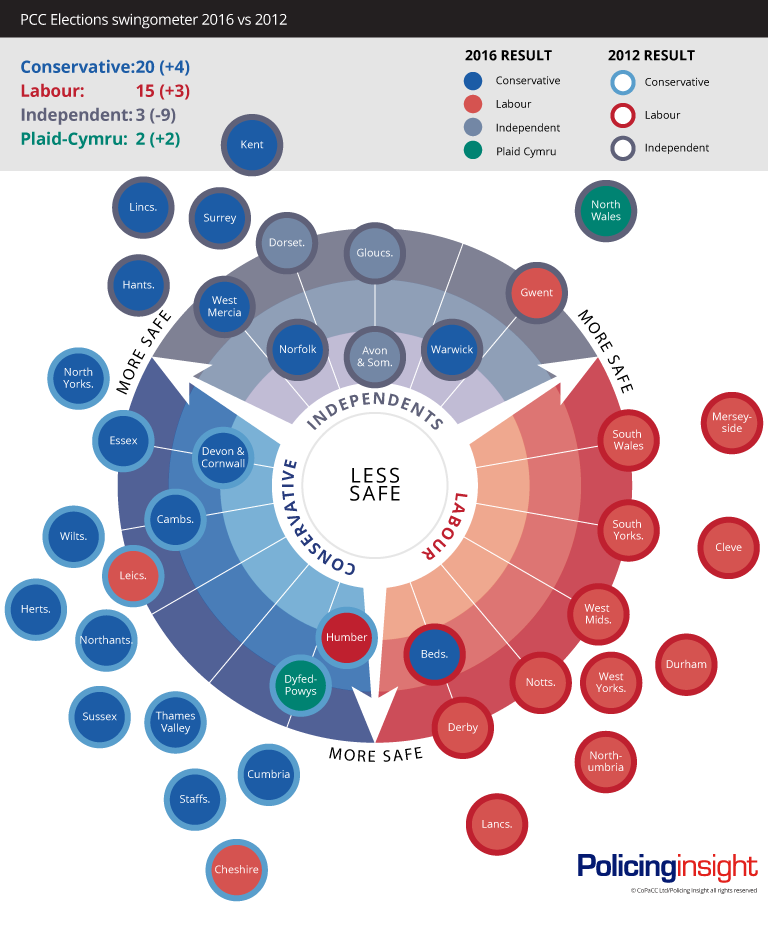

So just how safe are the PCCs in the 2021 Elections?

I’ve looked at a few of the specific factors that might impact the outcomes of the 2021 elections, taking into account the margins in 2016, the relative number and diversity of candidates, whether the incumbent PCC is fighting again and whether the availability of significant UKIP votes from 2016 will be a factor.

Blue and red rosettes at the ready

The very safest seats are those with the highest margins in the 2016 elections and the existing incumbent fighting again. Seven Conservative, five Labour and one Independent appear to be in this grouping with little doubt about the outcome.

Conservative: Cumbria, Essex, Hertfordshire, Lincolnshire, Suffolk, Sussex, West Mercia

Labour: Gwent, Northumbria, Nottinghamshire, South Wales and South Yorkshire

Independent: Gloucestershire

Further very safe seats had the highest margins in 2016 (and in some cases 2012 too) but the incumbent is stepping down; despite this I feel the seats in Durham, Leicestershire and Merseyside are still very safe for Labour, while North Yorkshire and Wiltshire should be bankers for the Conservatives.

Also in the ‘very safe’ seats I have included Northamptonshire – there have not been strong margins in Northamptonshire but the Conservative candidate has prevailed comfortably in both 2012 and 2016.

Should be comfortable – but beware banana skins

The ‘quite safe’ seats are those which at first glance appear to be safe, but have factors that may throw the results. With some seats it can be as simple as the incumbent stepping down and casting some doubt on the outcome, such as in Cambridgeshire (Conservative). In other seats – such as Hampshire (Conservative) – there is a record of strong margins, but with both the incumbent stepping down and an increase in candidates, the vote share could be affected. The movement of UKIP’s share of the votes may also be a factor; for example, Cleveland (Labour) has seen significant margins previously, but with the incumbent stepping down and significant UKIP votes now up for grabs, the Conservative candidate may be feeling encouraged.

West Midlands (Labour) is particularly interesting, with a popular PCC stepping down, significant UKIP votes to fight for and a recently elected Conservative mayor suggesting that a Conservative upset might be on the cards.

So too is Surrey, where the Conservative candidate who triumphed in 2016 then went on to give up his party affiliation during his term in office, and is restanding this year as an independent; although the current Conservative candidate is likely to emerge as the winner, the independent opposition (both from the most recent PCC, and the previous PCC who is also standing on an independent ticket) could represent a potential banana skin.

Tight tussles

There’s just four seats in my ‘quite unsafe’ category – Derbyshire (Labour), Kent and Warwickshire (both Conservative), and North Wales (Plaid Cymru) – and generally these are here due to narrow margins in previous elections. In North Wales, the Plaid Cymru PCC prevailed only in the second round after coming second in the first round, so the allocation of UKIP votes could have a significant impact.

In Kent there were narrow margins in 2016, but UKIP polled closest to the successful Conservative PCC candidate, so with the party not running this year, it depends where those votes go. To a lesser degree UKIP votes may also be factor for the other two.

All bets are off!

The ‘very unsafe’ seats are where things get very interesting, with four (two Independent and one each for Conservative and Labour) looking at risk.

In Avon & Somerset (Independent), there were very close margins between the Independent, Conservative and Labour candidates, and with the incumbent PCC stepping down it’s all up for grabs.

Again in Bedfordshire (Conservative), there were very narrow margins in 2012 and 2016 with a Labour PCC in 2012 and a slim Conservative victory in 2016. There are several Liberal Democrat, Independent and English Democrat candidates with a significant cumulative vote share in 2016 who might affect that slim margin.

In Cheshire (Labour), the Conservatives lost the seat by a slim margin and they may win the seat back if they benefit from the UKIP vote share.

In Dorset there were strong margins for the popular Independent PCC, but he has stepped down; with several candidates (Conservative, Labour, Liberal Democrat, Independent and Green) running and a significant UKIP vote share available, the result here is far from certain.

The map below, ‘How safe are PCCs in 2021 Elections?’, shows the political affiliation of each PCC after the 2016 PCC Elections with the representative colour graduated to reflect how safe, in my opinion, each seat is. (Note Surrey shows as Conservative but the PCC became independent later – the colour reflects how safe it is from a Conservative perspective).

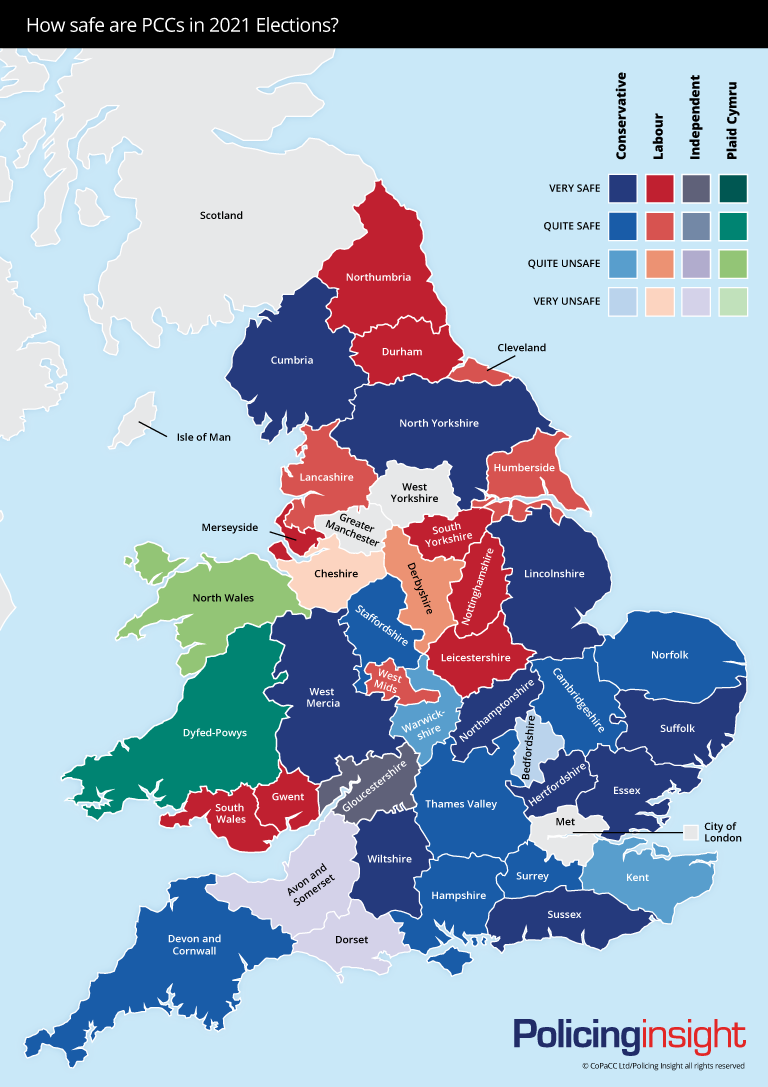

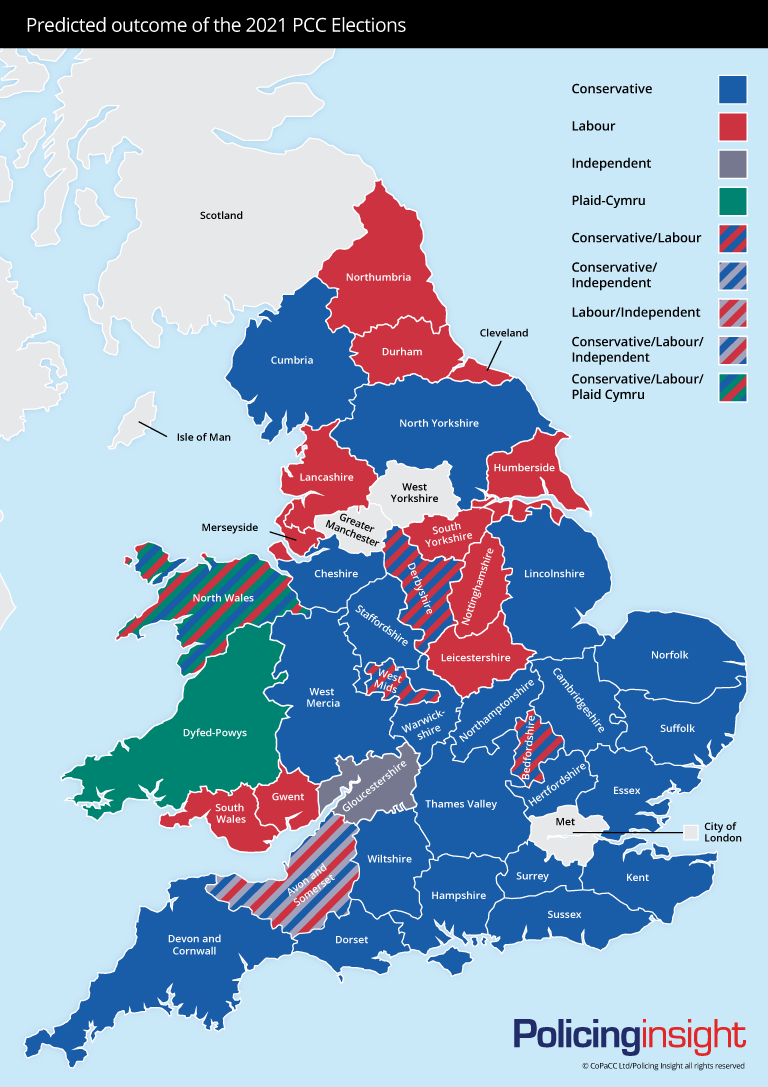

This article is very much my personal view and I suspect as many will disagree as agree with my analysis, but I’ve stuck my neck out further (whether in bravery or foolishness, I’ll let you decide!), and set out my predictions for the 2021 elections in the map below. You will see that far from being brave I’ve still sat on the fence, with five regions I just can’t call.

Why not let me and our readers know your thoughts on the outcome of the PCC Elections 2021 in the comments below.

Related articles

PCC ELECTIONS 2021: Candidates now confirmed, but – boy! – are they male dominated

PCC ELECTIONS 2021: Candidates now confirmed, but – boy! – are they male dominated

With less than two months to go to the police and crime commissioner elections for the English and Welsh forces, Policing Insight is launching its in-depth coverage. We’ll be constantly updating our tracker so you’ll be able to check out the candidates as they declare their intention to stand. Policing Insight’s Publisher Bernard Rix takes a look at the field so far.

All change: Policing governance is a hot topic once again

All change: Policing governance is a hot topic once again

The PCC elections are set to take place in May. Deloitte’s fourth report into police and crime commissioners is also due out the same month and will enable new and returning PCCs to optimise their role at a time of considerable change in policing. Deloitte’s Frances Lysak explains the focus of this latest report.

Learning the lessons: What previous PCC elections can tell us about this year’s contest

Learning the lessons: What previous PCC elections can tell us about this year’s contest

This May, in England and Wales, the public will go to the polls to elect their local police and crime commissioner. Professor Peter Joyce and Dr Wendy Laverick examine the lessons to be learnt from the previous two elections in 2012 and 2016 and what prospective candidates are likely to focus on in 2020.

There’s (another) election on the horizon: The PCC race for 2020

There’s (another) election on the horizon: The PCC race for 2020

While the focus of attention is on the upcoming general election, candidates for the next round of PCC elections are also becoming clear. Nina Champion, Director of the Criminal Justice Alliance, and Phil Bowen, Director of the Centre for Justice Innovation, look at how the race could affect criminal justice policy.

In the West Midlands contest it appears that the Conservative candidate, a young Sikh, is hoping to gain votes through a “bounce” from the efforts of the national government. That is a moot point to me, but the latest polls do show a growing margin over Labour nationally. The Conservatives rely on support from Dudley, Solihull, Walsall and to an extent Wolverhampton to counter the mass Labour votes from Birmingham.

Whether the contest for the Combined Authority Mayor helps is very unclear, again Andy Street may be hoping to have a similar “bounce”. For many voters I suspect the Mayor’s role is peripheral compared to local councils.

The interesting factor will be how the other candidates second preferences and onwards are allocated. One acute observer of the Birmingham political scene thought a few weeks ago now that Julie Hambleton would gain many ex-Labour votes and those who think justice for the B’ham Pub Bombings (1974) is still missing – most of her second preferences would go to the Tory. Desmond Jaidoo is not expected to do well, he is an inner city advocate and if his supporters do vote their second preferences would go to Labour.

Like all previous such elections a lot will depend on the turnout, whether in person or postal votes. Note, in Birmingham there is NOT a city-wide election for councillors, only five seats in by-elections. This may mean turnout may be quite low.

Given the low turnout that these elections have previously attracted, is it not pertinent to consider the breakdown of Force areas by the other elections that are taking place at the same time? In Leicestershire for example the City of Leicester is a unitary authority and is not holding elections this year whereas the remainder of the County have County Council elections. Therefore there’s an argument that the Tories are probably nailed on to win contrary to the suggestion here that it is a safe Labour controlled Force.

Excellent point, @Stuart! If I’d incorporated that further level of analysis, I’m inclined to agree that Leicestershire isn’t the Labour shoo-in I’d suggested. We’ll know the result soon enough, of course – just around ten days to go before the vote.