All high-income countries have experienced similar trends, and there is scientific consensus that the decline in crime is a real phenomenon.

Seventy-eight per cent of people in England and Wales think that crime has gone up in the last few years, according to the latest survey. But the data on actual crime shows the exact opposite.

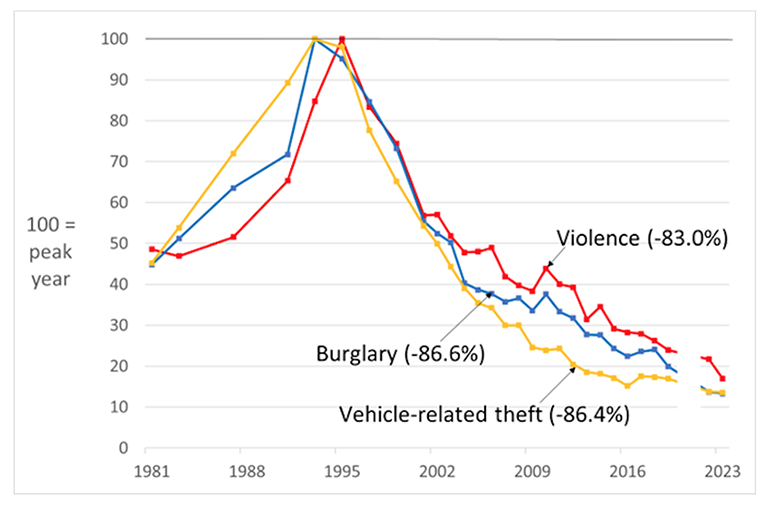

As of 2024, violence, burglary and car crime have been declining for 30 years and by close to 90%, according to the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) – our best indicator of true crime levels. Unlike police data, the CSEW is not subject to variations in reporting and recording.

The drop in violence includes domestic violence and other violence against women. Anti-social behaviour has similarly declined. While increased fraud and computer misuse now make up half of crime, this mainly reflects how far the rates of other crimes have fallen.

All high-income countries have experienced similar trends, and there is scientific consensus that the decline in crime is a real phenomenon.

Data via Office for National Statistics; Author provided (no reuse)

There is strong research evidence that security improvements were responsible for the drop. This is most obvious with vehicle electronic immobilisers and door deadlocks, and better household security – stronger door frames, double-glazed windows and security fittings – along with an avalanche of security in shopping centres, sports stadiums, schools, businesses and elsewhere. Quite simply, it became more difficult to commit crimes.

Decreases in crimes often committed by teenagers, such as joyriding or burglary, had a multiplying effect: when teenagers could no longer commit these easy ‘debut crimes’ they did not progress to longer criminal careers.

Decreases in crimes often committed by teenagers, such as joyriding or burglary, had a multiplying effect: when teenagers could no longer commit these easy “debut crimes” they did not progress to longer criminal careers.

There are, of course, exceptions. Some places, times and crime types had a less pronounced decline or even an increase. For many years, phone theft was an exception to the general decline in theft. Cybercrime, measured by the CSEW as fraud and computer misuse, has increased and is the most prominent exception.

But this increase was not due to thwarted burglars and car thieves switching targets: the skillset, resources and rewards for cybercrime are very different. Rather, it reflects new crime opportunities facilitated by the internet.

Preventive policy and practice is slowly getting better at closing off opportunities for computer misuse, but work is needed to accelerate those prevention efforts.

The perception gap

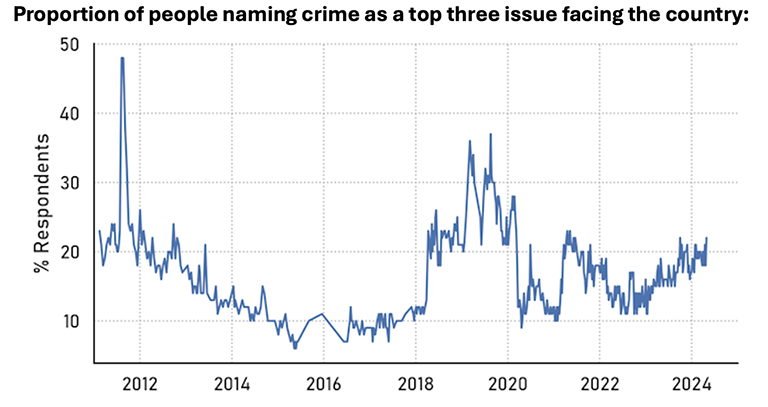

So why is there such a gulf between public perception and the reality of crime trends? A regular YouGov poll asks respondents for their top three concerns from a broad set of issues.

Concern about crime went from a low in 2016 (when people were more concerned with Brexit), quadrupled by 2019 and plummeted during the pandemic when people had other worries. But in the last year, the public’s concern about crime has risen again.

Data via Office for National Statistics; Author provided (no reuse)

There are many possible explanations for this, of which the first is poor information. A study published in 1998 found that “people who watch a lot of television or who read a lot of newspapers will be exposed to a steady diet of crime stories” that do not reflect official statistics.

The old news media adage “if it bleeds, it leads” reflects how violent news stories, including crime increases and serious crimes, capture public attention. Knife crime grabs headlines in the UK, but our shock at individual incidents is testament to their rarity and our relative success in controlling violence – many gun crimes do not make the news in the US.

Most recent terrorist attacks in the UK have featured knives (plus a thwarted Liverpool bomber), but there is little discussion of how this indicates that measures to restrict guns and bomb-making resources are effective.

Political rhetoric can also skew perceptions, particularly in the run-up to elections. During the recent local elections, the Conservatives were widely criticised for an advert portraying London as “a crime capital of the world” (using a video of New York), while Labour has also made reference to high levels of crime under the current government.

We are unlikely to be able to change political agendas or journalists’ approach to reporting. But governments should be taking a more rational approach to crime that is based on evidence, not public perception.

There are also some “crime drop deniers”, who have vested interests in crime not declining due to, for example, fear of budget cuts. One of us (Graham) worked with a former police chief who routinely denied the existence of declining crime.

Despite the evidence of crime rates dropping, some concerns are justified. Victims, along with their families and friends, have legitimate concerns, particularly as crime is more likely to recur against the same people and at the same places.

And, while the trend is clear, there are nevertheless localised increases in some types of offending. When these relate to harmful and emotive issues like knife crime in London, for example, it is natural that this might have a substantial influence.

We are unlikely to be able to change political agendas or journalists’ approach to reporting. But governments should be taking a more rational approach to crime that is based on evidence, not public perception.

Local governments need to keep on top of their local crime hotspots: problem bars and clubs where crime occurs, shops where shoplifting is concentrated, local road traffic offence hotspots and so on. The common theme here is how crime concentrates.

National government, meanwhile, should lead on reducing crime opportunities via national-level levers. Only national government can influence social media platforms and websites that host online crime and encourage larger businesses to improve manufacturing, retailing and service industry practices.

The positive story around crime rarely makes headlines, but this should not put us off from learning the lessons borne out in the data. We know this can work from past success, but it took decades to get car makers to improve vehicle security and to get secured-by-design ideas in building regulations. Society needs to move more quickly.

This article first appeared on The Conversation, and is republished under a Creative Commons Licence; you can read the original here.

About the Authors

Dr Toby Davies is Associate Professor in Criminal Justice Data Analytics at the University of Leeds. A quantitative criminologist with interest in spatial analysis, networks and computational methods, he completed his Doctorate at UCL and spent three years as a research associate on the Crime, Policing and Citizenship project, before becoming a Lecturer and Associate Professor in 2021; he joined Leeds in 2023. Toby has worked with the West Yorkshire, Thames Valley and West Midlands forces, and has provided analysis to other agencies including the London Mayor’s Office for Policing & Crime and the UK Home Office.

Dr Toby Davies is Associate Professor in Criminal Justice Data Analytics at the University of Leeds. A quantitative criminologist with interest in spatial analysis, networks and computational methods, he completed his Doctorate at UCL and spent three years as a research associate on the Crime, Policing and Citizenship project, before becoming a Lecturer and Associate Professor in 2021; he joined Leeds in 2023. Toby has worked with the West Yorkshire, Thames Valley and West Midlands forces, and has provided analysis to other agencies including the London Mayor’s Office for Policing & Crime and the UK Home Office.

Graham Farrell is Professor of Crime Science at the University of Leeds, having previously been a professor at universities in Canada (Simon Fraser) the US (Rutgers, Cincinnati), and Loughborough University, and deputy research director at the Police Foundation, Washington DC. His earlier career included working as an international civil servant at the UN in Vienna, Research Associate at the Centre for Criminological Research at Oxford University, and research assistant at the Home Office. His research interests are in crime science (particularly situational crime prevention) with a current focus on the international crime drop.

Graham Farrell is Professor of Crime Science at the University of Leeds, having previously been a professor at universities in Canada (Simon Fraser) the US (Rutgers, Cincinnati), and Loughborough University, and deputy research director at the Police Foundation, Washington DC. His earlier career included working as an international civil servant at the UN in Vienna, Research Associate at the Centre for Criminological Research at Oxford University, and research assistant at the Home Office. His research interests are in crime science (particularly situational crime prevention) with a current focus on the international crime drop.

Picture © Alphotographic / iStock

Related articles

Whisper it quietly, but crime is down – so why is no-one talking about it?

Whisper it quietly, but crime is down – so why is no-one talking about it?

The latest statistics for England and Wales indicate that levels of recorded crime have fallen to an all-time low, yet there has been little mention of the significant drop by the media, the Government or forces themselves; in this first of two articles, Policing Insight’s Ian Wiggett looks at the latest crime data and longer-term trends in crime, and why the apparent success in crime reduction remains something of a secret.

Crime is down, but police performance is now measured on actions as much as results

Crime is down, but police performance is now measured on actions as much as results

The latest statistics for England and Wales indicate that levels of recorded crime have fallen to an all-time low, yet there has been little mention of the significant drop by the media, the Government or forces themselves; in this second of two articles, Policing Insight’s Ian Wiggett considers the implications for how police performance is judged.

Interesting read. Aside of any issues with officer numbers, why does it feel like demand has increased? Additionally, are people reporting less? Many members of the public have said: “I don’t see the point, nothing gets done”, “This has been going on ages”, “I thought someone else would do it”, etc. etc. All phrases I’ve heard from victims and witnesses and in just general conversation with members of public. Is there a public apathy towards police? Afterall, it’s not like the police are viewed favourably in the media or often supported.