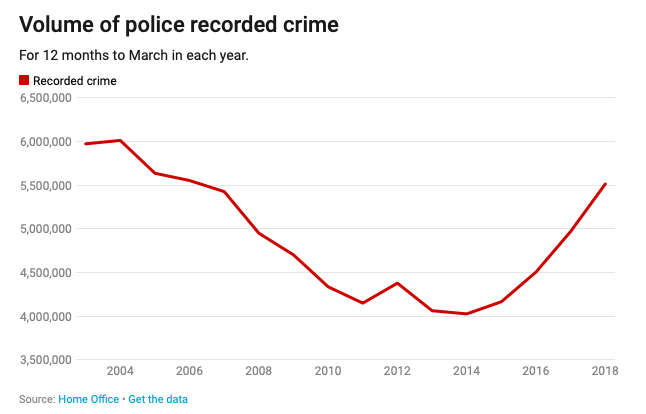

Offences recorded by police forces in England and Wales have been rising steeply since 2014, according to figures published by the Office for National Statistics.

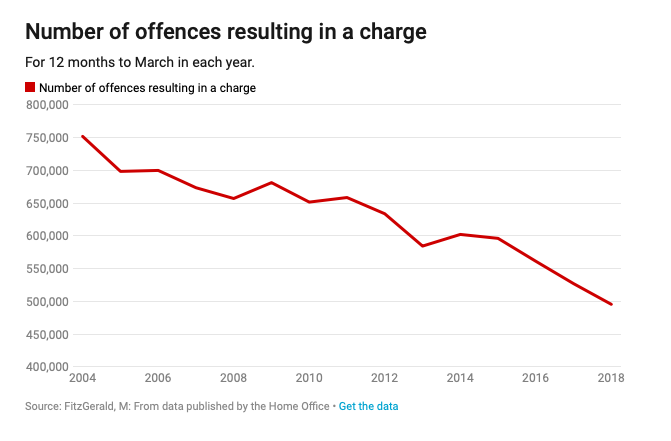

While the figure for recorded crime rose by more than a million, the number of offences where the police held to account those responsible fell by nearly 300,000.

However, the ONS doesn’t publish figures showing the related “detection rates” – the proportion of these offences for which police have also identified those responsible.

Yet annual figures for police detections have been published by the Home Office for many years, and these show a fall in detection rates since 2014.

In the 12 months to the end of March 2018, while the figure for recorded crime rose by more than a million compared to four years earlier, the number of offences where the police held to account those responsible fell by nearly 300,000.

Paradox

To begin to unravel this seeming paradox – of offences going up but the number of them being detected by the police going down – requires an appreciation of the developments in the police recording of crime in recent years and the context in which these took place.

Crime had been reducing since 2003. The police had also begun to meet a further target Labour set them in 2004 to increase detection rates.

Soon after becoming home secretary in the coalition government of 2010, Theresa May announced that she was abolishing policing targets. The only “mission” of the police, she insisted, was to reduce crime.

Yet the first policing targets set by the Labour government in 1997 also aimed to reduce crime. Although forces were slow to meet these expectations, crime had been reducing since 2003. The police had also begun to meet a further target Labour set them in 2004 to increase detection rates.

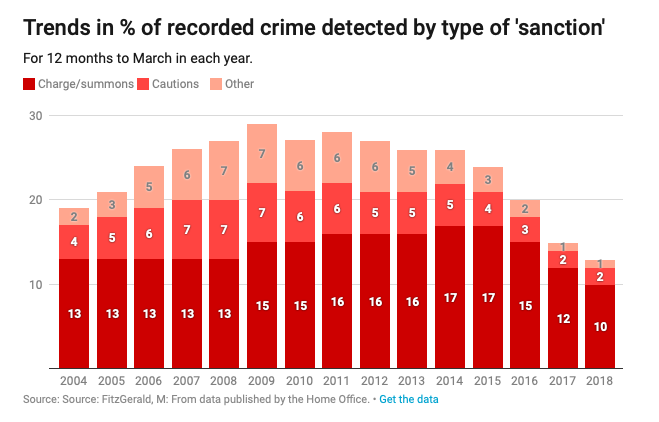

Labour’s new 2004 target applied only to detections where the police had formally held the suspects to account.

This meant either charging the suspect to be tried in court or applying one of three out-of-court sanctions: a caution or reprimand, an on-the-street sanction in the form of either a penalty notice for disorder, or a cannabis warning.

For the first three years, police forces met Labour’s commitment to increase the number of crimes for which an offender was brought to justice almost exclusively by using the three out-of-court sanctions, rather than by charging suspects.

Since these sanctions are available only for offences that don’t necessarily have to be tried in court, initially the offenders brought to justice were mainly responsible for less serious offences.

As the graphs below show, the number of offences resulting in a charge simply fell in line with recorded crime for three years after the detections target was introduced – but in 2008-9 it showed a sudden surge. So by the time Labour left office in 2010, 16% to 17% of recorded crimes resulted in a charge, compared to 13% prior to 2004.

A sudden increase

Once May abolished policing targets in 2010, it seemed in principle that detection rates might fall, because the pressure on the police had eased.

But for four further years, the number of crimes recorded by the police continued to fall and the proportion of offences resulting in a charge simply went back to following the same trend.

The picture changed dramatically from 2014, following the report of an inquiry by MPs on the Public Administration Select Committee (PASC).

It laid bare the strategies forces had employed to avoid including as many crime reports as necessary to ensure that the figures they submitted supported claims that the public had become safer.

It very publicly laid bare the range of strategies forces had employed to avoid including as many crime reports as necessary to ensure that the figures they submitted to the Home Office supported the claims made by a succession of home secretaries, including May, for more than a decade, that the public had become safer, since with every passing year crime continued to fall.

Following the publication of the PASC report in 2014, the ONS immediately withdrew its official approval from the police recorded crime figures, though it continued to publish them.

These figures continued to get steeper by the year and by March 2018, the overall number of crimes recorded in the previous 12 months had risen for the fourth year in a row.

But here’s the paradox: as soon as recorded crime started to rise, the number of offences resulting in a charge or summons actually fell, and has continued to fall with each successive year. Between 2013-14 and 2017-18 it fell by 18%, from 602,390 to 495,655, despite a rise of 37% in crimes recorded by the police over the same period. This seems largely to have gone unnoticed until it was highlighted in a BBC Panorama programme in 2018.

No suspect identified

One possible reason for this oversight is that since 2014, crime detection rates have no longer been published. Instead, they’ve been replaced by figures in a new series of Home Office reports entitled Outcomes of Crime England and Wales. From April 2013, all 43 local police forces and the British Transport Police have been required to record the final status (or “outcome”) they assigned to every offence they record, including those which had not resulted in a detection of any sort.

All forces have now been providing complete outcomes figures to the Home Office since the 2015-16 financial year, with each recorded crime assigned one of 20 outcome codes. The outcome category that has covered by far the largest number of recorded offences in each year is “Investigation Complete – No Suspect Identified”. The reports have consistently shown that 48% of all recorded crimes are finalised on this basis – and yet the term is extraordinarily ambiguous.

It may refer to crimes subject to intensive investigation, which have nonetheless failed conclusively to identify any suspects. But it may equally refer to large numbers of offences reported to the police, which as an investigation by Channel’s 4 Dispatches programme revealed in October 2018, are increasingly being “screened out” by the police. This practice means that the reports are simply recorded as crimes but they receive no active attention from the police. The extent of screening out varies between forces but the process is commonly applied to those offences the public are most likely to report to the police, such as theft of and from cars.

Crime unsolved

Meanwhile, an appendix table in the Home Office outcome reports still makes it possible to track the overall trend in detections resulting in both charges and the other “sanctions”, which previously counted towards the Labour-era targets. As the graph below shows, the “sanction detection” rate had halved in four years, falling from 26% in the year to the end of March 2014 to 13% by the same time in 2018.

After four years of rising crime, 288,000 fewer offences had resulted in those responsible being identified by the police and subject to some type of formal sanction. Although charges have always accounted for the largest single type of sanction detection, they accounted for little more than a third of the total fall. It was out-of-court sanctions that accounted for 181,000 – or two thirds – of the shortfall, a point that has been hitherto overlooked.

This means that, while concerns about the fall in charges are belatedly being recognised following the Panorama programme, maintaining a focus on these alone serves to mask a very much larger problem of the overall fall in police detection rates.

Taken together with the findings of the Dispatches programme, this points to the conclusion that the increasing failure of the police to detect the crimes they record disproportionately affects those offences which – in law – are treated as the least serious. Yet these include the offences the public is most likely to experience and to report to the police.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

Interesting articles, though I’d say it’s hardly a paradox. More a simple calculation…

Fewer officers investigating + Exponential increase in crime workload = Less time spent investigating each crime (and therefore resulting in fewer charges, due to volume and or quality of each investigation)

Yes the removal of targets might have some part to play, as for example senior leaders and their middle-management level have prioritised more ‘Victim Safeguarding’ outcomes over ‘Offender Sanction’ outcomes, as they are increasingly having to choose between the two, given the calculation above. There must also be some relation to the types of offences (i.e. if the increase of offences is more the sort that get ‘screened out’ or have low probability of a sanction), indirect consequences of where forces choose to put their diminishing resources, societal changes, plus increased evidential thresholds and/or less time with changes in recent years in CPS standards and time limits.

What appears currently in Policing Insight should ideally have formed the intoduction to a much longer piece; but this ran up against the word limit for a Conversation article. It was therefore published as the first of two articles, the second of which has yet to appear.

I appreciate that, as it stands, the main thrust of the article is to highlight the fall in the number of recorded offences resulting in a charge and that this will come as no surprise to police officers who will see it as an inevitable consequence of the fall in their number. However, the article was written for a non-police readership – potentially including journalists. As yet the latter appeared not even to have noticed the fact that the Home Office had ceased publishing detection rates, still less to discover what the figures would by now have looked like, until the Panorama programme first drew attention to the fall in charges.

It hardly needs to be pointed out here that detection rates cannot be inferred from charges alone. The overall fall in sanction detections is very much larger still; and this will be the starting point for part two. Without wanting to give too much away, part two will look at the range of factors which have created this situation (including the fall in police numbers) and will highlight the concerns the media and others should urgently be raising about the long-term consequences of the police’s increasing inability to respond to the crimes most commonly experienced by the public – i.e. rather than continuing to be distracted by wrangling over whether crime is ‘really’ rising (as evidenced by the police recorded crime figures) or whether to stick with the official line that the estimates based on the government’s Crime Survey are the only reliable measure of trends……

Watch this space!

Marian

Thanks Marlan, I look forward to Part Deux!

Thanks for the nudge Adrian. It comes in the wake of extensive – and often misleading – media coverage of the most recent crime statistics published by ONS. Under cover of which, the Home Office also released its most recent ‘Outcomes’ report for the same period on the same day which appears to have gone completely unnoticed…..

Yet what would once have been ‘Sanction Detections’ have now fall from 14 per cent of police recorded crime in the year to the end of September 2017 to 12 per cent a year later.